-

-

Yellowstone Riverboat History

[Extracted “in-part” from the Daily Herald Records, and

John G. MacDonald: “History of Navigation on the Yellowstone”,

Master Thesis, MSU 1950; and excerpts from the research books noted in the text

below]

Revised Thursday, May 31, 2012

The era of river navigation began in 1836, when a

new riverboat Yellowstone made its way up the Missouri

to the mouth of the Yellowstone

River  . Earlier however, in 1831, Pierre Chouteau of St.

Louis had a small flat bottom steamboat also named YELLOWSTONE and he brought a cargo of goods up the river

. Earlier however, in 1831, Pierre Chouteau of St.

Louis had a small flat bottom steamboat also named YELLOWSTONE and he brought a cargo of goods up the river  . This trip revolutionized the Missouri river

fur trade by their being able to make the trip in a few weeks, which formerly

took a whole season. Next was apparently Major Taylor, who came to St. Louis to work on the Mississippi steamboats. He became a

riverboat captain and was master of the steamer "Clairmont" which he

piloted into the Yellowstone

River in 1845 on a

trading expedition for Pierre Chouteau’s American Fur Company. Serious

navigation on the Yellowstone River began in 1873

. This trip revolutionized the Missouri river

fur trade by their being able to make the trip in a few weeks, which formerly

took a whole season. Next was apparently Major Taylor, who came to St. Louis to work on the Mississippi steamboats. He became a

riverboat captain and was master of the steamer "Clairmont" which he

piloted into the Yellowstone

River in 1845 on a

trading expedition for Pierre Chouteau’s American Fur Company. Serious

navigation on the Yellowstone River began in 1873  , and from that time until the NPR (Northern Pacific Railroad) passed

through Billings, traffic was quite heavy In 1883 the NPR made a special deal

for freight hauling that virtually eliminated all steamboat trade. The boats

started out carrying supplies for the pioneers, and taking buffalo hides back.

This changed to carrying supplies for the military, then for the railroad. Many

of these boats were short lived, and their origins or travels haven’t been

fully recorded. In reality they are flat-bottomed wooden packet boats, but are

referred to as “steamers.” Most were

stern-wheelers, but a few were side-wheelers. Steamers Mary McDonald and the Sioux City were reported

in early Billings Gazette articles, but dates and locations of travel not

established. Some of the boats had collapsing smoke stacks; some had smoke

stacks that could be laid down to pass under bridges. Some of the greatest

research endeavors into the operation of steamboats were created by:

, and from that time until the NPR (Northern Pacific Railroad) passed

through Billings, traffic was quite heavy In 1883 the NPR made a special deal

for freight hauling that virtually eliminated all steamboat trade. The boats

started out carrying supplies for the pioneers, and taking buffalo hides back.

This changed to carrying supplies for the military, then for the railroad. Many

of these boats were short lived, and their origins or travels haven’t been

fully recorded. In reality they are flat-bottomed wooden packet boats, but are

referred to as “steamers.” Most were

stern-wheelers, but a few were side-wheelers. Steamers Mary McDonald and the Sioux City were reported

in early Billings Gazette articles, but dates and locations of travel not

established. Some of the boats had collapsing smoke stacks; some had smoke

stacks that could be laid down to pass under bridges. Some of the greatest

research endeavors into the operation of steamboats were created by:

1)

“Days of the

Steamboats”, William H. Evans, Parents Magazine 1967.

2)

“Wild River,

Wooden Boats”, Michael Gillespie: Undated, Heritage Press.

3)

“Old West

River Boaters”, Charles

L. Convis. (IBSN 1-892156-09-1), Undated

4) “Steamboating on the Upper Missouri River”,

William E. Lass. University

of Nebraska Press.

Undated

5) A Brief History of Steamboating on the Missouri River

with an emphasis on the Boonslick Area, by Robert L. Dwyer

These first-hand

research books tell virtually all you would ever want to know. The extraction

below comes from these and other first-hand witnesses. Of interest, is the huge

amount of wood needed to propel these boats upstream; 1-2 cords per river mile.

The authors are to be commended for their diligence and research expertise in

preparing their books.

Dates

for travel on the Yellowstone

River:

1817

The first boat reportedly on the Missouri was the Constitution

in October. Tickets were sold for an excursion trip from St. Louis to Bellefontaine, eight miles

distant. (Site visitor to Dyer’s homepage reported the information, obtained

from the Missouri Gazette of October 4, 1817.)

1818-1819

The government initiated an effort to use riverboats to

carry expedition parties (mainly the Corps of Engineers or various Military

commands) into the area frequented by the Sioux, this being the Upper Missouri

River & the Yellowstone River the Independence[i],

commissioned by Elias Rector, was second.

The first steamship constructed specifically for river

travel was the Western Engineer. It

was the third boat to ascend the Missouri.

“To scare the Indians and to keep them from causing trouble, the Western

Engineer was made to look as if she were riding on the back of a sea monster[ii].”

At the bow was a huge snake’s head, with an open – red mouth. Exhaust steam

from the engines hissed out of the mouth, giving the appearance of a real

monster that was breathing fire. It did actually frighten the Sioux, who had

never even seen a normal riverboat. It had a bullet-proof pilot house.This boat

also traveled up the Missouri

for a distance of about 200 miles, but it set the stage for future

developments. On June 9, 1819 the vessel left St. Louis, along with a large group of

smaller boats carrying military supplies. Two weeks after the Independence

returned to St. Louis, a scientific expedition

led by Col. Henry Atkinson & Major Stephen Long, started up the Missouri River in four[iii] steamboats

and nine keelboats.

James Johnson, having strong

political supporters, got the military contract without bidding, and with no

regard of cost to build five steamers (in addition to the Western Engineer) to

support the military’s first Yellowstone Expedition. [The Yellowstone Expedition term would be

used over and over for virtually each of the treks into Montana, causing much error in future

reporting of events.] The ships he had constructed were not designed for

the rigors imposed by the Missouri, let alone

the Yellowstone. These boats were the Thomas

Jefferson, Expedition, R.M. Johnson, J.C. Calhoun and Exchange. This

military expedition’s primary purpose was to establish an American presence at

the mouth of the Yellowstone Rive to discourage the British in the area. Since

the boats only made it as far as Council

Bluffs, a fort was established there. The boats

transported 1,100 escort troops and supplies under the command of Col.

Atkinson. Major Long headed up the scientific team aboard the Western Engineer.

William D. Hubbell was hired on

as a clerk on the R. M. Johnson. Years later he recounted the adventure[iv].

The Western Engineer accompanied the other boats,

but was far in advance, and had to wait for them to catch up. It arrived alone

at Ft. Osage

on August 1st, then passed the future site of Ft.

Leavenworth on the 18th,

and stayed a week at Fort Lisa (five miles below Council Bluffs.) The others were 470 miles

downstream. It was decided to winter here and await the others. A year later

four of the boats reached Council Bluffs, where

the expedition ended far short of its goal to ascend the Yellowstone.

Congress terminated all funding.

1820

The only reported boats on the Missouri were the Missouri

Packet and the Expedition. The Missouri Packet arrived at Franklin on May 5th, and on the return trip it

hit a snag and sunk not far from Franklin.

Both boats carried supplies for the troops at Cantonment Missouri.

1830-1831

Kenneth McKinzie established the

American Fur Company in the remote regions of the Upper Missouri and Yellowstone Rivers starting in 1827. He decided to

cut operating costs for these outlying posts by building a steamboat to service

them. He approached Pierre Choteau, Jr., agent in St. Louis with the idea. After some

persuasion, Pierre presented the proposal to the

New York

office in August 1830. A contractor in Louisville

was hired to build the little boat. It was 130 feet long, and had a beam of

19-feet, with a 6-foot hold. It drew 6-feet of water when loaded, and was

patterned after the Mississippi

boats, which required a substantial amount of water to travel, rather than the

shallow draft that was needed on the western waters. It was delivered to St. Louis on April 10, 1831, in time for it to make its

maiden voyage to Fort

Union. Pierre Chouteau was

passenger on this trip. Commanded by Captain B. Young, it left St.

Louis on 20 April and all went well until the end of May when it

reached the confluence of the Niobrara. Low

water prevented any further progress. Pierre

called for help to unload the supplies and carry them upriver by land. Under a

lighter load the Yellowstone continued upriver to Fort Tecumseh.

On June 19th it could go no further, and returned to St. Louis on July 15th,

carrying a load of buffalo robes, furs and 10,000 pounds of buffalo tongues.

This trip revolutionized the Missouri river

fur trade by their being able to make the trip in a few weeks, which formerly

took a whole season, although it had problems.

1832

The Yellowstone made its

second trip up the Missouri, traveling 1,800

miles to Fort Union without difficulty, arriving June

17th. This boat showed that the river could be tamed, and the era of

Steamboating on the western rivers was to begin in earnest. The flow of fur

trade was such that there was no need to travel beyond Fort Union.

1850

The El

Paso, commanded by Captain John Duroc, in an interest to get

fame, traveled just past the mouth of the Milk River.

They named this point on the Missouri “El Paso.”

1860

The military units stationed in

the west started to use riverboats as a means to transport goods and personnel.

The government representative generally contracted for a boat on a day-to-day

basis, which was very costly. This method was used almost exclusively until

1866 when they issued contracts for service on a yearly basis. Under this

method they paid a fee based on destination, type of goods and personnel to be

carried. The Chippewa and Key West

were reported to be the first riverboats to reach Fort

Benton, on the Missouri

River.

1863/1864

During the winter months,

General Pope conceived of a new plan for his operations in the Indian country

along the Missouri River, and assigned General

Sully the task. For this he planned to constructed four new posts to be located

at: Devil’s Lake, James River, Long Lake outlet, and one on the Yellowstone near Fort Alexander.

The last three were to be placed on the emigrant routes leading to the gold mines

in Montana.

Red tape prevented General Sully from getting started as planned.

1864

General Sully mustered about 2,200 men, two batteries

(e.g., 12 artillery pieces), 300 teams and 300 beef steers. The men and

equipment marched west by land while steamers carried the supplies. At Farm Island

the Dakota Militia joined his forces. Moving from there to the outlet of Long Lake,

he established Fort Rice on the west bank of the Missouri

(about 8-miles above the outlet of the Cannonball River.)

Seven boats were used to carry supplies to Fort Rice.

The quartermaster misdirected 1,000 tons of supplies to Farm Island,

where they were dumped, and causing great delay in recovery of the supplies.

Steamer Alone and Chippewa Falls [drawing 12” water] each

carrying about fifty tons of freight; and a little corn for the animals arrived

at the mouth of the Big Horn River to meet General Sully’s Command. By the time

General Sully was ready to depart Fort

Rice he had over 4,000

soldiers under his command. The steamer

Island City was the third boat in this group,

carrying aboard nearly all of the command’s much needed corn, struck a snag

near Fort Union and sank. This shortage of Corn

prevented General Sully from proceeding west of the Yellowstone.

The remaining steamers attempted to go upstream from the Big Horn, but a rapid

shoal rendered it impossible  . The two remaining steamers

then went downstream carrying Sully’s supplies, until the water became too low.

The supplies were off-loaded and transported by the command. At the outlet of

the Yellowstone General Sully selected the site for Fort Buford.

(Constructed in 1866 when supplies were made available.)

. The two remaining steamers

then went downstream carrying Sully’s supplies, until the water became too low.

The supplies were off-loaded and transported by the command. At the outlet of

the Yellowstone General Sully selected the site for Fort Buford.

(Constructed in 1866 when supplies were made available.)

1867

By 1867 steamboat traffic had been established between St.

Louis and Fort

Benton. By 1881 there

were 25 to 30 steamers plying the Missouri River with headquarters at Bismarck and Fort

Benton. In 1877 exports

worth $1,270,600 were carried out and in 1881 imports of $5,214,000 were

carried in. Steamers declined after the advent of the railroad in 1887. The

"Amelia Poe", a sternwheeler, hit a snag south of Frazer and sunk on

May 28, 1868. The "Big Horn" a like fate 4 miles west ' of Poplar on

May 8, 1883. Indians found cutting wood for the steamers profitable. The

Steamer "Chippewa" burned and exploded on the south side of the

Missouri River a few miles below Poplar

River on June 22, 1861.[v]

1869

Steamer Alone, with Captain RB Bailey & Cutler;

and then again with Captain Abe Hutchison, went upstream on the Yellowstone

about 45 miles to a place called Crane’s Ranch; to locate General Sully’s

command so they could deliver the army’s supplies.

1870-1872

No Record.

1873 – Start of Serious

Steamboat Operation

Three major companies were vied for fur trade and commerce on the Upper

Missouri Area[vi].

·

Missouri River Transportation Company based at

Yankton (15 boats)

·

Northwest Transportation Company (7 boats)

·

Kountz Line (4 boats)

In August William J. Kountz who had worked with Sanford B. Coulson

earlier, announced that he would no longer be associated with the Coulson Line

(Missouri River Transportation Company), and would now operate exclusively with

NPR. Thus he formed the Northern Pacific Railroad Line [steamboat line]

stationed at Bismarck.

The military eventually realized the importance of having steamboats to carry

supplies and troops. Thus the era of ‘Steamboating’ started to flourish.

Steamer Key West, commanded by General George A Forsythe (Major &

Brevet General, Aide to General Sherman), commandeered  the Coulson riverboat at Fort

Lincoln along with Grant

Marsh as Captain; and his crew. The Army thought the area was probably filled

with hostile Sioux warriors and General Forsythe was assigned a mission to

ascend the Yellowstone River to examine the channel and the countryside as

far as the Powder River. Boat officers were:

the Coulson riverboat at Fort

Lincoln along with Grant

Marsh as Captain; and his crew. The Army thought the area was probably filled

with hostile Sioux warriors and General Forsythe was assigned a mission to

ascend the Yellowstone River to examine the channel and the countryside as

far as the Powder River. Boat officers were:

Grant

Marsh (pilot and captain)

Nick

Beusen (pilot and clerk)

Charlie

Dietz (mate)

John

Sacklett (first engineer)

There was no available military support at Fort Lincoln, so General

Forsythe made arrangements to pick up soldiers from Fort Buford (Colonel WB

Hazen  commanded five companies in his regiment stationed at Fort Buford)

He also hired two French-Indian guides who claimed to know the upper Missouri

River very well. After a short time it was apparent that these guides were

lost, and of no value. Captain Marsh then recommended that they see if

Yellowstone Kelly (age 23) would be at Wood Chopper’s Point, and ask for his

services, which he accepted

commanded five companies in his regiment stationed at Fort Buford)

He also hired two French-Indian guides who claimed to know the upper Missouri

River very well. After a short time it was apparent that these guides were

lost, and of no value. Captain Marsh then recommended that they see if

Yellowstone Kelly (age 23) would be at Wood Chopper’s Point, and ask for his

services, which he accepted  . There was no room for his horse on this trip, so he only brought his

pack and rifle aboard. The accommodations were cramped (only 31 staterooms

available at the time) and after picking up soldiers at Fort Buford,

Kelly had to seek out a better place to bed down. During the trek General

Forsythe made detailed sketches of the river’s course and terrain.

. There was no room for his horse on this trip, so he only brought his

pack and rifle aboard. The accommodations were cramped (only 31 staterooms

available at the time) and after picking up soldiers at Fort Buford,

Kelly had to seek out a better place to bed down. During the trek General

Forsythe made detailed sketches of the river’s course and terrain.

At Fort Buford they stopped and picked up two

companies of the 6th Infantry under Captains M. Bryant and D. H. Murdock.

Departing Fort Buford

they entered the Yellowstone

River. After 125 miles

they reached Glendive Creek, and General Forsythe thought this would be the

place where the NPR would eventually cross the Yellowstone.

Accordingly he examined the area and established a suitable place where a

supply depot could be constructed, disposing of the bulk of his military

supplies to be used later by the Infantry approaching overland by foot. The

supplies were arranged such that it formed a sort of barricade. On the seventh

day of travel they arrived within two miles of the Powder

River, stopping there on May 6th. Further journey was not possible

due to low water and a large expanse of rocks blocking their path. Later in the

season it was evident that they could traverse further upstream. This

demonstrated to the Army that the river was navigable for at least 245 miles.

During this journey, the first on the river for Captain Marsh, he [reportedly]

kept a logbook of the journey, as was apparently custom for first-time treks

into new waters. He and his pilot, Captain Beusen (listed as both Clerk and

Pilot; and the first person to receive a license for piloting on the Yellowstone) recorded the river conditions, driftwood

availability, channels, chutes, and named many of the visible mountain &

local area terrain elements. All notable objects were named, excepting those

identified earlier by William Clark in 1806. Some notable ones were:

Forsythe

Butte (First prominent Bluff on east bank of the Yellowstone just below its

confluence with the Missouri

named in honor of General Forsythe)

Cut

Nose Butte, Chimney Rock and Diamond Island

were named because of their shapes.

A

few miles above Diamond Island there were seven small islands; Captain Marsh

named them: Seven

Sisters Islands

(in remembrance of his seven sisters.)

Crittenden

Island was named for General TL Crittenden, Commander of the 17th

Infantry garrisoned at several posts along the Missouri.

Mary

Island was attributed to the chambermaid of the Key West, and wife of ship

steward “Dutch Jake.”

Reno

Island was named for Major M Reno, of the 7th Cavalry.

Schindel Island was named for Captain Schindel of

the 6th Infantry.

Bryant’s

Buttes were named for Major M Bryant, Commanding Escort for the Key West.

Edgerly Island was named for Lt WS Edgerly of

the 7th Cavalry.

Monroe

Island was named for Monroe Marsh, Captain Marsh’s brother.

DeRussy

Rapids was named for Issac D DeRussy, later a Colonel of the 14th

Infantry

McCune

Rapids was named for one of Captain Marsh’s friend in St Loui.s

Barr’s

Bluff was also named for another of Captain Marsh’s friends.

Stanley’s Point (located just before the Powder

River) was named for Colonel Stanley, a member of the 22nd

Infantry.

Sheridan’s Bluffs (located across the river from the mouth

of the Powder River and now called “Sheridan Butte”) was named for Lt-General Sheridan.

Accompanying the army on the trip was Dan Scott, correspondent for the

Sioux City Journal plus the following Army officers stationed at Fort Buford:

2nd Lt RT Jacobs, Jr., 2nd Lt George B Walker,

Captain DH Murdock,

2nd Lt Josiah Chance, 2nd Lt Thomas G Townsend,

Captain M Bryant (Brevet Major), Captain ER Ames, and 1st Lt Fred W

Thibaut.

Note

that 2nd Lt Townsend would play a very important role in future

trips up the Yellowstone, and he is the one

who supplied the current military map for the area. This map is believed

to be the one created by Capt Reynolds etal when they surveyed the vast Indian

regions in 1859 & 1860. [Published in 1867 and very accurately places the Yellowstone River & tributaries with the earth’s

coordinates.] Also accompanying the troops was Captain Ludlow of the Corps of

Engineers.

Capt. Marsh returned to the Missouri River

in just 9 days after leaving the area. During the upstream journey, Yellowstone

Kelly would walk ahead of the riverboat, and check out the area for signs of

Indians and game, and generally be waiting for the boat with a supply of meat

for all to enjoy. He reported that typically he left the military campsites

about 1 am, and bedded down a long distant from the boat and crew so that he

could hear sounds of game. He would rise early and hunt for food, being very

cautions not to run into any Indians. Elk were so numerous along the river it

became quite obvious to him why the Indians called it “Elk

River.” No Indians, however, were noted during this trip. The

following pilot license was found in the Grant Marsh files:

(North Dakota Historical Society 16 mm mf-Grant

Marsh file, apparently a gag, as no Indians were seen)

To whom it may concern:

This

is to certify that Captain Grant Marsh has given satisfactory evidence to me

–General Inspector – of his capabilities to navigate the waters of the Yellowstone river and is hereby duly licensed to run,

buck and warp up the river to his heart’s content.

His...

Sitting Bull _____x (mark)

Inspector General of the Yellowstone, and Chief Scalp Lifter of the Hostiles.

May

14, 1873

In June three Steamers, Peninah, Key West, and Far West,

loaded supplies at Bismarck for the army troops who had left earlier from Fort

Rice, and were traveling cross-country under the command of General Stanley.

Peninah

- Captain Abner Shaw

Key West - Captain Grant

Marsh

Far West - Captain Mart Coulson

“Earlier in May, 1873, (See Above) the third expedition to the

Yellowstone was organized at Fort

Rice and commanded by

General Stanley  . The composition was: Troops A, B, C, E, F, G, H, K, L, M, 7th

Cavalry

. The composition was: Troops A, B, C, E, F, G, H, K, L, M, 7th

Cavalry  ; Companies C, 6th; B, C, F, H, 8th; A, D, E, F, H, I, 9th; A, B, H,

17th; Headquarters and B, E, H, I, K, 22d Infantry, and a detachment of

Arikaree Indian scouts. This expedition, accompanied by a large wagon train

loaded with supplies left Fort Rice, June 20th, arriving at a point to cross

the Yellowstone, about fifteen miles above where the town of Glendive is now

located, on July 31st.

; Companies C, 6th; B, C, F, H, 8th; A, D, E, F, H, I, 9th; A, B, H,

17th; Headquarters and B, E, H, I, K, 22d Infantry, and a detachment of

Arikaree Indian scouts. This expedition, accompanied by a large wagon train

loaded with supplies left Fort Rice, June 20th, arriving at a point to cross

the Yellowstone, about fifteen miles above where the town of Glendive is now

located, on July 31st.

The Key

West had previously been ordered to first go to

Yankton and pick up passengers, and then join the other two boats.  General Custer ordered Captain Marsh to take on board most of the

women and children of the regiment, as well as the personal baggage of the

officers. Custer’s command would be mainly marching along the west bank of the Missouri on the upland

prairies where the trails were smoother. The voyage and command march lasted

several weeks. During the journey the boat docked near where the soldiers were

camping whenever possible. They arrived at Bismarck on June 20th, and the

three boats started their journey upstream.

General Custer ordered Captain Marsh to take on board most of the

women and children of the regiment, as well as the personal baggage of the

officers. Custer’s command would be mainly marching along the west bank of the Missouri on the upland

prairies where the trails were smoother. The voyage and command march lasted

several weeks. During the journey the boat docked near where the soldiers were

camping whenever possible. They arrived at Bismarck on June 20th, and the

three boats started their journey upstream.

After reaching the Yellowstone

River the survey party

and the accompanying large military escort proceeded south along the east bank

of the river as far as Pompey's Pillar, but not without opposition from the

Indians, who evidently had concluded that the surveying had gone far enough. On

August 4th, just opposite to where Fort

Keogh was built, they

attacked the advance guard, killing the veterinary surgeon, sutler and one

soldier of the 7th Cavalry. The

cavalry’s regiment pursued the “savages” for several miles, killing a number of

them. On August 11th, the cavalry, camped opposite the mouth of the Big Horn

River, again encountered

the Indians and a desperate fight ensued with loss of life on both sides.

Lieut. Charles Braden, 7th Cavalry, was severely wounded. Lieut. H. H. Ketchum,

adjutant 22d Infantry and adjutant-general of the expedition, who was

temporarily with General Custer then commanding the 7th Cavalry, had his horse

shot under him. Upon the approach of the infantry the Indians abandoned the

field. That night the battalion of the 22d occupied the advance posts and

exchanged shots with the Indians, who tried to approach the camp, probably to

stampede the horses, mules and cattle herd. During the afternoon of that day

the artillery detachment, which was composed of men of the 22d and commanded by

Lieutenant Webster, was obliged to shell the timber along the bank of the Yellowstone to dislodge a large body of Indians, who were

evidently preparing to impede the next day's march. They were dispersed and

seen again only in small parties, one of which fired into the camp at Pompey's

Pillar and then beat a hasty retreat, having done no damage. From Pompey's Pillar

the expedition marched north to the Musselshell

River, thence westward to the Great

Porcupine, following it until the Yellowstone

was again reached. This was a new and unexplored country and it was a very

difficult thing to take a large command and wagon train through it. There was a

great deal of hardship, especially from frequently having to drink alkaline

water and sometimes having no water at all. The command marched into Fort Lincoln,

arriving there September 22d; thence the companies proceeded to their

respective stations. They had marched during the expedition over twelve hundred

miles and returned in excellent physical condition.”

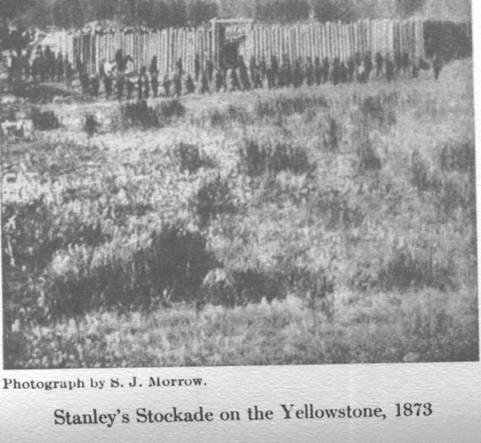

Each boat, carrying advance supplies for the military and surveyors,

dropped them off at the Glendive Creek depot, created earlier in May by General

Forsythe, and two immediately returned; the Key West stopped at Fort

Buford to pick up a company from the 6th Infantry under Captain

Hawkins, who remained on the boat for the duration of the campaign. At Glendive

the Key West

remained to ferry various personnel assigned to support the surveying efforts

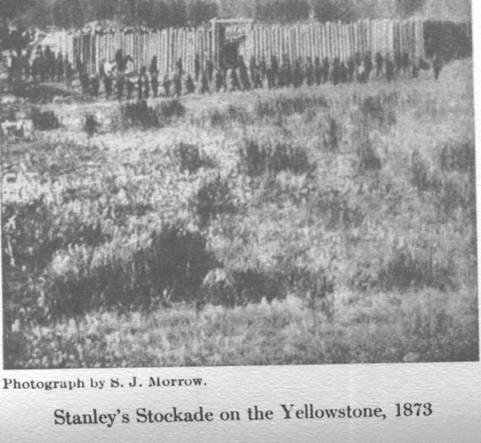

of the NPR and other duties, and the soldiers started to erect a stockade at

the supply station. Part of General Custer’s 7th Cavalry was the

first contingent to arrive at the depot, some 12 days later. The commands as

they arrived were ferried across the Yellowstone, to a point about 15-20 miles

upstream named “Stanley’s

Stockade.” Heavy rains hampered the support command’s main column and they took

41 days to complete the march (July 31st). During this march,

General Custer had several invited guests, including R. Graham Frost (St Louis,

and son of Confederate General DM Frost), Lord Clifford and another English

Nobleman. The NPR engineer in charge of the survey group was General TL Rosser,

Custer’s roommate at West Point, who had

previously joined the Confederate Army, and had fought against Custer’s command.

(Photo insert from Parmly Library – Scrapbook Files)

The

Key West

continued for several days to ferry men and supplies from Glendive to the

temporary fort at Stanley’s Stockade until all were transferred. Captain

Marsh then took the group of surveyors fifty miles upstream, where they

surveyed that section of the valley west of Powder River (approximately 2-1/2

miles from the Baker’s Battlefield site – where in 1872 the survey was

suspended). All of these surveys took place on the west side of the

river, and were later discarded when a separate small team, acting under

special orders, (1880-1881) created the eastern side route

The

Key West

continued for several days to ferry men and supplies from Glendive to the

temporary fort at Stanley’s Stockade until all were transferred. Captain

Marsh then took the group of surveyors fifty miles upstream, where they

surveyed that section of the valley west of Powder River (approximately 2-1/2

miles from the Baker’s Battlefield site – where in 1872 the survey was

suspended). All of these surveys took place on the west side of the

river, and were later discarded when a separate small team, acting under

special orders, (1880-1881) created the eastern side route  . It was at this time that Father Stephen (Catholic)

arrived alone, having followed the army’s trail from Fort Rice.

The survey efforts were completed, and the army started their return. One

company of the 17th Infantry and two troops of the 7th

Cavalry were left to guard the Stockade.

. It was at this time that Father Stephen (Catholic)

arrived alone, having followed the army’s trail from Fort Rice.

The survey efforts were completed, and the army started their return. One

company of the 17th Infantry and two troops of the 7th

Cavalry were left to guard the Stockade.

Marsh was then ordered to carry some mail that just arrived from Fort Rice,

back upstream to the Powder River contingent before they left for Bismarck. From there it

returned to the Stockade. On one of the ferry trips in mid August they met the Josephine

(Captain John Todd) coming up river loaded with some more supplies to be

delivered at Glendive Creek. Captain Marsh transferred to her and sent the Key West back to Bismarck

(Fort Abraham Lincoln).

In mid-August the Steamer Josephine (recently

completed at Freedom, PA, and a much smaller boat), was pressed into immediate

service  . The main body of the Army Command under General Stanley, delayed due

to bad weather, took an additional three weeks for them to reach the Yellowstone battle sites near the Big Horn. They fought

the Sioux at various places along the Yellowstone as far south as Pompey’s

Pillar

. The main body of the Army Command under General Stanley, delayed due

to bad weather, took an additional three weeks for them to reach the Yellowstone battle sites near the Big Horn. They fought

the Sioux at various places along the Yellowstone as far south as Pompey’s

Pillar  , and for some distance inland towards the Musselshell.

With them was Lt. Charles Braden, who was shot through the left leg by a rifle

ball, shattering the bone from hip to knee

, and for some distance inland towards the Musselshell.

With them was Lt. Charles Braden, who was shot through the left leg by a rifle

ball, shattering the bone from hip to knee  . He was carried on a stretcher back to where the Josephine was tied

up, and transferred to her. The Josephine then continued to ferry the command

across the Yellowstone in preparation for their long march back to Fort Rice.

It then returned to Fort Buford on the 17th with nine companies of

troops and 28 officers from the 8th & 9th Infantry

Battalions

. He was carried on a stretcher back to where the Josephine was tied

up, and transferred to her. The Josephine then continued to ferry the command

across the Yellowstone in preparation for their long march back to Fort Rice.

It then returned to Fort Buford on the 17th with nine companies of

troops and 28 officers from the 8th & 9th Infantry

Battalions  and conveyed to Sioux City.

Stopping at Fort Buford, on the way down stream, Captain Marsh picked up

William H. Seward (Clerk to Paymaster, Major William Smith), who was assigned

to pay off the troops at various posts along the river. He had one more post to

visit, Fort Stevenson. He also received word when he

departed that his wife had given birth, and he was very anxious to return home.

Captain Marsh was under strict orders not to make any unnecessary stops while

returning, but the paymaster’s clerk obviously needed some assistance, since

there was no transportation from Buford to Stevenson, or further travel

downstream.

and conveyed to Sioux City.

Stopping at Fort Buford, on the way down stream, Captain Marsh picked up

William H. Seward (Clerk to Paymaster, Major William Smith), who was assigned

to pay off the troops at various posts along the river. He had one more post to

visit, Fort Stevenson. He also received word when he

departed that his wife had given birth, and he was very anxious to return home.

Captain Marsh was under strict orders not to make any unnecessary stops while

returning, but the paymaster’s clerk obviously needed some assistance, since

there was no transportation from Buford to Stevenson, or further travel

downstream.

From this Captain Marsh came up with an immediate solution:

Calling his First Engineer, Charlie

Echols, he asked “Charlie, don’t you

think the engine valves ought to be ground?” Echols intently scrutinized the

face of his chief. “Well, I don’t know but they had, captain,” he replied

with a grin.

“Take you about half a day, won’t it

Charlie?”

“Yes.

Reckon it will; about half a day.”

“Alright, we’ll do it

at Fort Stevenson.”

They took Seward aboard and delivered him to Fort Stevenson

to make payroll. When Seward completed paying off the troops he rejoined the

boat and the Josephine immediately started south, dropping Seward off at Bismarck so he could catch

the first train east. Eight years later Seward, wife and daughter, made a

special trip west to meet with Captain Marsh to thank him for his kindness.

The next stop was at Fort

Lincoln where Lt Braden was sent to

the post hospital, and awaited further journey to St Paul. A year later, and with no ability to

recover or to return to active duty, he retired. [Braden spent much of his

time compiling rosters and other Army source materials.] Braden left his

campaign hat on board, and Captain Marsh would not allow it to be removed from

Braden’s cabin, a memento of one soldier’s exceptional courage.

1874

No trips on the Yellowstone were

recorded; however, the Josephine made several commercial trips between

Yankton and Fort Benton. Carroll was founded near the

mouth of the Musselshell River and served as a freight landing point for

overland shipment by wagon trains across Judith

Basin and into Helena. The Diamond R. Transportation

Company, backed by Carroll townspeople, enjoyed a brisk business for two years.

The shortcut took ten days less shipment time than the Fort Benton

delivery route. [By 1876 the route was virtually eliminated due to numerous

Sioux war party attacks, and steamers bypassed the stop.]

1875

On 19 May, General Sherman ordered Col’s Forsythe and Grant, under orders from the War

Department, to commandeer the Steamer

Josephine for an Expedition up the Yellowstone to determine how far they could go, and to

determine places for military support to the army. The boat reached a

clear-water area on June 7th, about 1-1/2 mile west of Duck Creek Bridge, Billings,

MT, and then turned

around [vii] No civilians, excepting for the boat’s crew, were

permitted on board. Four mounted scouts were allowed along with a number of

soldiers.

While the

Josephine was en route on the Yellowstone with Colonel Forsythe, the War

Department, Engineering Section issued a direct order on June 14th,

to commandeer the Josephine and make a trip to the Yellowstone.

They actually meant, “to survey the headwaters of the Yellowstone

River where Yellowstone Park

is located,” but it was called “Yellowstone Expedition!” For this activity the

Josephine traveled on the Missouri River and discharged its passengers at Carroll, Montana, and

then returned to Fort

Buford on July 15th.

The members of this crew by numerous researchers have mistakenly been thought

to be the ones on the previous trip to Duck Creek! Captain Ludlow conducted

a survey of the Yellowstone River from Bozeman

Pass to its headwaters in Yellowstone Park. He returned on August 16th.

This is the trip that carried four Smithsonian Scientists mentioned in Captain

Grant Marsh’s 1907 letter to the President, and in Hanson’s book: “Conquest of

the Missouri”, pgs 221-223. It seems that after this was published, newspapers

and others intermixed the two trips. [Refer

to original notes.]

1876

General Terry was sent into the Sioux Territory

to fight. From the previous trips it was clear that supplies needed by the Army

could be transported easily by “steamer” to the mouth of the Big Horn River. Boats used to provide the

supplies were: Far West, Tiger, Benton, Silver Lake,

Carroll, Yellowstone, Durfee and Josephine. By

1883, Josephine was the only boat on the river. After the Custer Battle,

Captain Marsh, commanding the Far West, on

June 30th, took on board 52 wounded, and Comanche, Custer’s injured horse.

He delivered them to Fort Lincoln and Bismarck.

The need for better fort

protection, as identified in General Pope’s 1863 original plan became evident,

and Congress committed $200,000 for two posts on the Yellowstone[viii]:

Fort Keogh (near the mouth of Tongue River, and usually referred to as the

Tongue River Post), and Fort Custer (located at the mouth of the Big Horn). On

July 24th the Quartermaster General of the Department of Dakota,

issued orders to provide building supplies to 2nd Lt. Drubb (Bismarck

Quartermaster). After learning the posts were to be built on the Yellowstone,

he first instructed the Key West to be loaded with lumber and shingles,

proceed to Fort Buford to take on a military guard, and go up the Yellowstone

(but not past Tongue River), look for General Forsythe, and leave supplies for

him at the new fort location. He later added five more Coulson boats to

transport materials, plus Wilder’s Silver

Lake and Peck’s Nellie

Peck. To accommodate the heavy military demand, the Coulson line had to charter

six more boats from their rivals.

John O’Brien, a local Billings’ Indian War Veteran, was stationed at Fort Richardson.

He was ordered to the Cheyenne Agency. He took the train to Yankton, and the

steamer Nellie Peck to the agency.[ix]

1877

Fort Custer and Fort

Keogh were under

construction, and the boat traffic increased. The government opened a new bidding

contest. Twenty firms competed, and John B. Davis won the bid. He then

organized the Yellowstone Transportation Company, with John Reaney as manager[x].

Not having boats of their own, and unable to secure the lease of Missouri

riverboats from the other bidders, the company leased heavy Mississippi

Riverboats & crews, plus built towing barges to carry coal and supplies for

the journey; wood being too scarce. The pressures of delivery were too tough to

handle, and the freighting needs could not be met on schedule. One disaster

after another befell the company. Loss of all the supplies and the boat

Osceola, which was blown to pieces in a storm at the mouth of the Powder River, basically ended the short contract with the

Yellowstone Transportation Company. Lt. Drubb then loaded Coulson’s boats with

supplies anytime a Davis

boat was unavailable. By fall all of Davis’s

boats were unavailable. In late August the Davis contract was completed and he left the

area. (In 1878 he rebid the new

contract, but failed to win.) On October 10th, it was reported that

over 600 tons of military supplies still needed shipment. Providing supplies

were: Far West, Western, Tiger, Yellowstone, Peninah, General Meade, General

Sherman, Florence, Mayer, Osceola, Savannah, Kendall, Weaver, Victoria,

Arkansas, Fanchon, JC Fletcher, Tidal Wave, Silver City,

JH Rankin (sunk at the mouth of O’Fallon Creek), Rosebud, Big Horn, Fontanelle,

General Custer, and Josephine. By 1883, only the Meade, Rosebud, Big Horn

& Josephine remained. A Jewish man, by the name of Basinski, opened up

a tent store near the ferry on the north side of the Yellowstone,

across from Terry’s Landing. This was the start of Junction City. General Sherman and his staff

took the Rosebud

from Fort Lincoln

and onto the Yellowstone

River, arriving at its

mouth on July 13th. On the 17th he arrived at Tongue River, where General Miles was in process of

establishing a post there. On the 18th they arrived at the Little

Big Horn junction with the Big

Horn River

; and there he established a new post on the 21st. The river was

flowing eight-miles/hour in the bends. The General Sherman was stationed there,

and was used to run traffic & supplies from the Yellowstone

to the post. Sherman

took the Rosebud and examined the river for a good spot to offload there

military supplies. The river was too swift at the junction of the Big Horn with

the Yellowstone, so he selected a place three miles upstream on the south bank

of the Yellowstone for that purpose.

(Cantonment Terrry – directly southeast of where Junction City was located. It was a 30-mile

trek to the new fort by wagons.)

The Indian

Service released a split-supply contract in New York, with the C.K. Peck & C.M.

Primeau (associate of Peck). Five steamers were used to carry the supplies,

plus General Terry’s military freight. Coulson’s steamers were thus available

for other freighting activities. On one the 1877 trips, Thomas McGirl, who had

recently homesteaded on some land at the confluence of the Prior Creek with the

Yellowstone (later Huntley), went to Bismarck

and ordered some needed supplies for a trading post he was establishing. The

Josephine carried supplies for him, arriving at the end of May. At the McGirl

Trading post Captain Marsh took on a load of furs. From there he proceeded

upstream to where other homesteaders were reported to be residing. At this

time, all were absent, and the only probable apparent campsite (tent) was

Joseph MV Cochran’s, located at the site of the famed “Josephine Tree”. It was

here that the Josephine docked; and deLacy recorded the event. Captain Marsh

reported the docking as being June 7th. This simple date and location has been

interchanged with the actual June 6th, 1875 docking date when

Colonel Forsythe was exploring the Yellowstone

River, and stopping about

1-1/2 mile west of Duck Creek. Walter W. deLacy (see above sketch), in his 1878

survey notes reported:

The Josephine

reached “this fractional township situated at the eastern end of Clark’s Fork Bottom. It is bounded on the south and east

by the Yellowstone River, which has been navigated in 1877 to a

point within the township [Range 26E, Township 1S, Section 16] and a little

above [downstream from the boat’s position] the town of Coulson. The only timber in the township is

Cottonwoods along the Yellowstone

River and on the islands.

Tree marked by steamer ‘Josephine’ bears north 50 links distant, the highest

point ascended to by steamboats.” Captain Grant Marsh stated in a 1907

letter that he marked the tree “Josephine, June 7, 1875. On the 1878 survey map Walter deLacy recorded what was

actually carved on the tree, and reported it as “Highest point reached by a

steamboat in 1877.” There is no record of any tree being marked according to

the military report issued by Colonels Forsythe and Grant in 1875.

1878

Peck retained

part of the supply contract, and Coulson received all the rest. Supplies for

the Red Cloud & Spotted Tail agencies were estimated at 900 carloads. Nine

riverboats traveled the river, making 15 trips in total to Sherman, with some

going on to Terry’s Landing (opposite of Junction), and one to Camp Bertie

located near to Pompey’s Pillar. The supplies they delivered brought business

to freighters who hauled loads to Bozeman. Some went by stagecoach.

The steamers

Rosebud, Butte, Helena, Eclipse, General

Sherman, Batchelor, Big Horn, General Custer, Yellowstone, General Rucker,

General Terry, General Tompkins, Peninah, and General Meade made trips on the Yellowstone. Nine of these steamers made 15 trips, with

stops at Junction. At the time, Junction was on the “Outlaw Trail” a route from

Utah to Canada. George Parker (Butch

Cassidy) was one of the outlaws who used the trail.

1879

It was

reported by the Bismarck Tribune[xi]

that private shipments amounting to about 4,675 tons was equally divided

between the Coulson, Benton and Baker Lines. Shipments were made to all points

on the Missouri and Yellowstone River.

FY Batchelor

delivered 50 tons of merchandise to Terry’s Landing (South of Yellowstone,

across from Junction)

1880

Steamers Rosebud,

Helena, Butte,

Big Horn, Nellie Peck, General Terry, Batchelor, Western, and Josephine made

trips on the Yellowstone. Peninah II made its

last trip to Fort

Benton.

1881

Only the

Batchelor, Josephine, Rosebud, Big Horn, Helena,

Black Hills, and Eclipse were on the river.

Freight deliveries were made to:

May & June Miles City, Glendive, Fort

Keogh, Fort

Custer & Fort Buford

October Popular

River & Fort Buford

1882

Steam boating

on the Yellowstone

River essentially came to

a close, with the hauling of materials for NPR mainly by NPR #1 and #2. The

Eclipse made one trip, the General Terry one trip, and the F. Y. Batchelor made

four short trips, its last being to Junction City. Some minor excursions were made near the mouth of the Yellowstone until about 1910. Deliveries were:

April Little

Muddy, Fort Buford,

Miles City (beer)

June Fort Buford,

Popular River, Wolf

Point

During one of

these trips the Batchelor stopped at Guy’s Landing to deliver supplies.

T.C. Power

used the NPR for shipments to his Benton-Billings freight line. Business was so

profitable that he moved his warehouses to Billings to better serve the storage needs.

The FY Batchelor made two trips to Fort Custer from Myers. Once a week supplies

were delivered to Heman Clark at Coulson, where he was installing a waterworks

system for use by NPR at Billings. The steamer also delivered supplies for the

Winston Company (ST. Paul) who were laying track in the Billings area. During

the summer, supplies were delivered to the army stationed at various points

along the river to guard the workers while the track was being constructed.

On Tuesday August 22nd, NPR Locomotive #84 (W. Snyder, Engineer,

along with the construction engineer, and conductor, FB Smith) crossed the

Yellowstone River.

Northern

Pacific #2 was the tender for constructing the bridge over the Big Horn

River. Additionally it

took rail cars across the river while the bridge was being constructed.

1883-1884

No steamboats

on the Yellowstone, all were on the Missouri,

however, the FY Batchelor and the NPR #2, earlier in 1882 made it as far north

as Pease Bottom (12 miles below Junction

City, its destination) and had to wait until spring to

continue down river. While stuck in the ice Captain & Mrs. Woolfolk (NPR

#2) & gave a dance on the boat Because the accommodations had low ceilings,

Mrs Wolfolk and a friend Miss Rene Vander Power went over to the Batchelor to

arrange dinner tables for the party to come later. Suddenly the ice broke, and

the steamer turned sidewise against the current and the ice flows. The cables

of both boats were strained, and the crews quickly attacked more cables to

other trees for safety. The NPR in 1883 made a special contract with the two

foremost remaining steamboat companies that essentially sealed their fate: Fort

Benton Transportation Company (Owned by TC Power and organized in 1875) and

Missouri River Transportation Company (Owned by Coulson).

1.

Any imports or exports

of points on the Missouri above Bismarck, which also had

to be handled by the railroad, would be channeled through NPR.

2.

The steamboat

companies could not carry freight, which was delivered to the Missouri River

below Bismarck.

3.

The steamboat

companies could not carry freight destined for points on the NPR line.

4.

No steamboats would

trade on the Yellowstone

River, and:

5.

NPR would give the

steamboat companies the benefit of reduced rates and rebates.

Accordingly,

all riverboat trade in the Yellowstone

River Valley

was eliminated. All smaller riverboat companies in Montana were eliminated from competition;

and these two giants had very profitable years. In 1885 Coulson withdrew from

the Missouri

trade. The two remaining NPR boats (#1 and #2) were delivered to Bismarck in

May & June, thus ending the river travel.

1906

Captain Grant

Marsh carried concrete between Glendive and the Mondak Dam on the steamer Expansion.

In July he transported the Hon. Secretary of Interior, Mr. Garfield and

Senators Dixon and Carter of Montana and their party from Glendive to the

headgate of the irrigating ditch on the Expansion, and all agreed that the

navigation of the river should be conserved. This same Yellowstone River

has well served a mighty purpose in the past, in the pioneer days, and well deserves

the protecting hand of the government. From this meeting he wrote a letter in

1907 to President Roosevelt, protesting the potential damming of the Yellowstone.

Riverboat Summary

[Click on

image link (where available) to preview photographs and sketches of the

riverboat] Other referenced links are not available; just reference sites to

local source documents. Source material obtained from http://www.members.tripod.com riverboat

site & the above noted books. Please note that many of these steamers were

reconfigured over time, thus changing the dimensions and decks to better

accommodate the freight trade. Accordingly, there are various reports. There

appears to be no clear-cut identification for the multiple names assigned to

some steamers used in the local areas; Eclipse, Eclipse2. The ones listed below

from the numerous sources listed are attempted to be a summary of the launch

condition. Photographs are difficult to obtain at time of launch.

|

Name

|

Built-Lost

|

Length

(ft)

|

Width/Beam

(ft)

|

Hold

(ft)

|

Net Tonnage

|

Draft Unladen

|

Tonnage @ 3 Ft

|

Tonnage @ 2 Ft

|

Original Owner

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Alone

|

1850

|

|

|

|

|

12” @50 tons

|

|

|

|

|

Big Horn

|

|

177.4

|

31.3

|

4

|

293.86

|

|

192.1

|

85

|

|

|

Black Hills-1

|

|

193

|

32.6

|

4

|

370

|

|

212

|

85

|

|

|

Black Hills-2

|

1877-1884

|

135

|

27.5

|

4.5

|

|

|

|

Parts from Silver

Crescent

|

|

|

C. W. Meade

|

|

193

|

30.6

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Carroll

|

1875-1877

|

185.7

|

31

|

6

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Chippewa

|

1857-1861

|

160

|

30

|

|

173

|

12” @ 50 tons

|

|

|

|

|

Dakota[xii]

|

1879-1893

|

252

|

|

|

900+

|

|

|

|

|

|

E. H. Durfee

|

|

206

|

35

|

5.5

|

467.17

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eclipse

|

1852

|

350

|

76

|

9

|

1117

|

|

|

|

|

|

Eclipse (2)

|

1854-1860

|

150

|

27

|

4

|

156

|

|

|

|

Moore

|

|

Eclipse (3)

|

1862-1865

|

|

|

|

223

|

|

|

|

Moore

|

|

Eclipse (4)

|

1878-1887[xiii]

|

180

|

31

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

Moore

etal

|

|

Expansion

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Far

West[xiv]

|

1870-1883[xv]

|

189

|

33.5

|

5

|

357.81

|

20”

|

187.8[xvi]

|

60

|

Coulson

|

|

Florence

|

1857-1864[xvii]

|

200

|

34

|

|

399

|

|

|

|

|

|

Frank

Y. Batchelor

|

1878-1879[xviii]-1907

|

180

|

30

|

3.5 then 4

|

316

|

|

195.6

|

90

|

Leighton & Jordan

|

|

General Custer

|

1870-1879[xix]

|

182

|

28

|

3.8

|

|

|

|

|

Kountz

|

|

General D.H. Rucker

|

1878-1886[xx]

|

215

|

35

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

Kountz

|

|

General Meade

|

1875-1888[xxi]

|

192

|

30

|

4.3

|

|

|

|

|

Kountz

|

|

General Sherman[xxii]

|

-1884[xxiii]

|

|

|

|

243

|

|

|

|

US Gov’t

|

|

Helena[xxiv]

(Kehlor)

|

1878-1891[xxv]

|

195

|

32

|

4

|

352.31

|

|

205.5

|

70

|

Benton

|

|

Independence

|

1819

|

|

|

|

98

|

|

|

|

|

|

Island

City

|

1850?-1864[xxvi]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Jefferson

|

1819[xxvii]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

US Gov’t

|

|

Josephine (1881-on

Missouri)

|

1873-1907[xxviii]

|

178

|

31

|

4’6”

|

300.51

|

20”

|

180.7

|

70

|

Coulson

|

|

Key West[xxix]

|

1857-18__[xxx]

|

200

|

33

|

5’5”

|

422.6

|

20”

|

182.3

|

50

|

Coulson

|

|

Mary McDonald

|

C1867

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Osceola

|

-1877[xxxi]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Peninah

|

1868-1875[xxxii]

|

180

|

30

|

|

421

|

|

|

|

Kountz

|

|

Peninah #2

|

1876-1887[xxxiii]

|

172

|

27

|

5.6

|

|

|

|

|

Kountz

|

|

R . M. Johnson[xxxiv]

|

1819[xxxv]

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

US Gov’t

|

|

Rosebud

|

1877-1896[xxxvi]

|

177.4

|

31.3

|

4

|

|

|

|

|

Coulson

|

|

Silver

City

|

1860’s

|

190

|

35

|

|

350

|

|

|

|

Coulson

|

|

Sioux City[xxxvii]

|

1870-1873[xxxviii]

|

162.5

|

30

|

3.4

|

|

|

|

|

Cooper & Sawyer

|

|

Tidal Wave (Grand Pacific[xxxix])

|

1870-1884[xl]

|

160

|

36

|

5

|

476

|

|

|

|

Kountz (Kouns?)

|

|

Western

|

1872-1881[xli]

|

208

|

35

|

5’5”

|

475

|

|

|

|

Coulson

|

|

Western Engineer[xlii]

|

1819-

|

75

|

19/13

|

19”

|

|

19”[xliii]

|

|

|

US Army

|

|

Yellowstone[xliv]

|

1831-1833[xlv]

|

130

|

19

|

6

|

|

|

6 ft @75 tons

|

|

American Fur Co

|

-

-

![]() . Earlier however, in 1831, Pierre Chouteau of

. Earlier however, in 1831, Pierre Chouteau of ![]() . This trip revolutionized the

. This trip revolutionized the ![]() , and from that time until the NPR (Northern Pacific Railroad) passed

through Billings, traffic was quite heavy In 1883 the NPR made a special deal

for freight hauling that virtually eliminated all steamboat trade. The boats

started out carrying supplies for the pioneers, and taking buffalo hides back.

This changed to carrying supplies for the military, then for the railroad. Many

of these boats were short lived, and their origins or travels haven’t been

fully recorded. In reality they are flat-bottomed wooden packet boats, but are

referred to as “steamers.” Most were

stern-wheelers, but a few were side-wheelers. Steamers Mary McDonald and the

, and from that time until the NPR (Northern Pacific Railroad) passed

through Billings, traffic was quite heavy In 1883 the NPR made a special deal

for freight hauling that virtually eliminated all steamboat trade. The boats

started out carrying supplies for the pioneers, and taking buffalo hides back.

This changed to carrying supplies for the military, then for the railroad. Many

of these boats were short lived, and their origins or travels haven’t been

fully recorded. In reality they are flat-bottomed wooden packet boats, but are

referred to as “steamers.” Most were

stern-wheelers, but a few were side-wheelers. Steamers Mary McDonald and the

![]() . The two remaining steamers

then went downstream carrying Sully’s supplies, until the water became too low.

The supplies were off-loaded and transported by the command. At the outlet of

the Yellowstone General Sully selected the site for

. The two remaining steamers

then went downstream carrying Sully’s supplies, until the water became too low.

The supplies were off-loaded and transported by the command. At the outlet of

the Yellowstone General Sully selected the site for ![]()

![]() the Coulson riverboat at

the Coulson riverboat at ![]() commanded five companies in his regiment stationed at Fort Buford)

He also hired two French-Indian guides who claimed to know the upper Missouri

River very well. After a short time it was apparent that these guides were

lost, and of no value. Captain Marsh then recommended that they see if

Yellowstone Kelly (age 23) would be at Wood Chopper’s Point, and ask for his

services, which he accepted

commanded five companies in his regiment stationed at Fort Buford)

He also hired two French-Indian guides who claimed to know the upper Missouri

River very well. After a short time it was apparent that these guides were

lost, and of no value. Captain Marsh then recommended that they see if

Yellowstone Kelly (age 23) would be at Wood Chopper’s Point, and ask for his

services, which he accepted ![]() . There was no room for his horse on this trip, so he only brought his

pack and rifle aboard. The accommodations were cramped (only 31 staterooms

available at the time) and after picking up soldiers at

. There was no room for his horse on this trip, so he only brought his

pack and rifle aboard. The accommodations were cramped (only 31 staterooms

available at the time) and after picking up soldiers at ![]() . The composition was: Troops A, B, C, E, F, G, H, K, L, M, 7th

Cavalry

. The composition was: Troops A, B, C, E, F, G, H, K, L, M, 7th

Cavalry ![]() ; Companies C, 6th; B, C, F, H, 8th; A, D, E, F, H, I, 9th; A, B, H,

17th; Headquarters and B, E, H, I, K, 22d Infantry, and a detachment of

Arikaree Indian scouts. This expedition, accompanied by a large wagon train

loaded with supplies left Fort Rice, June 20th, arriving at a point to cross

the Yellowstone, about fifteen miles above where the town of Glendive is now

located, on July 31st.

; Companies C, 6th; B, C, F, H, 8th; A, D, E, F, H, I, 9th; A, B, H,

17th; Headquarters and B, E, H, I, K, 22d Infantry, and a detachment of

Arikaree Indian scouts. This expedition, accompanied by a large wagon train

loaded with supplies left Fort Rice, June 20th, arriving at a point to cross

the Yellowstone, about fifteen miles above where the town of Glendive is now

located, on July 31st. ![]() General Custer ordered Captain Marsh to take on board most of the

women and children of the regiment, as well as the personal baggage of the

officers. Custer’s command would be mainly marching along the west bank of the

General Custer ordered Captain Marsh to take on board most of the

women and children of the regiment, as well as the personal baggage of the

officers. Custer’s command would be mainly marching along the west bank of the  The

The

![]() . It was at this time that Father Stephen (Catholic)

arrived alone, having followed the army’s trail from

. It was at this time that Father Stephen (Catholic)

arrived alone, having followed the army’s trail from ![]() . The main body of the Army Command under General Stanley, delayed due

to bad weather, took an additional three weeks for them to reach the

. The main body of the Army Command under General Stanley, delayed due

to bad weather, took an additional three weeks for them to reach the ![]() , and for some distance inland towards the

, and for some distance inland towards the ![]() . He was carried on a stretcher back to where the Josephine was tied

up, and transferred to her. The Josephine then continued to ferry the command

across the Yellowstone in preparation for their long march back to

. He was carried on a stretcher back to where the Josephine was tied

up, and transferred to her. The Josephine then continued to ferry the command

across the Yellowstone in preparation for their long march back to ![]() and conveyed to

and conveyed to