Jim Bridger

Guide Information

Monday, May 28, 2012

The information presented below, through our sponsor, is used

to help identify where James (Jim) Bridger was during the periods he traversed

the western areas of the Indian Lands. This is developed to assist in locating

the critical wagon roads in the Yellowstone

Regions that he made or helped create and those that were identified at later

dates. As an adventurer, Bridger moved about the countryside, cutting through a

wide swath of terrain during his tenure as mountain man and guide. The

information presented below is compiled mainly from original manuscripts and

diaries of those who were with him at the time. Most of the extracts are

presented without change, but some have been adjusted to create normal sentence

structures for ease of reading and comprehension. Many of the local landmarks

discovered by he or his companions are discussed in depth so as to provide as

much insight into their discoveries as practical, and assign rightful

ownerships when possible. As with most discoveries, there is no single sole

ownership of such; but rather the claims belong to many, each with their own

tale of excitement. In piecing this listing together Stanley Vestals book “Jim Bridger” was used

as a timeline reference, and the source materials added to it for a more

complete understanding of the events. Of special interest are the Ashley

Expeditions, through which Bridger got his start as a mountain man in 1822.

Virtually all source materials and historical extracts relating to these

expeditions were created with the interest of the events that occurred, and not

the specific relation of the events to the hiring of men for support of the

trapping activities. These historical overlaps in history have been untangled

and presented as separate events to present a timeline for the significant

activities that Bridger undertook. The early years begin with mountain men

looking to make a fortune in furs. To help understand the major companies that

sought the fur trade claim in the local areas, these fur companies dominated

the region:

·

In 1670 when King Charles II of England granted a group of investors a charter

and a trading monopoly covering a vast region of northern North

America. The territory granted to "The Governor and Company

of Adventurers of England Trading into Hudson's

Bay" covered much of present-day Western Canada and parts of the Northern United States. Henry Kelsey, who was the first

European to see herds of buffalo on the plains of Western Canada, and Company

explorers such as Samuel Hearne and Anthony Henday opened large uncharted areas

of the North and West to commerce, trade and subsequent settlement. Canadian

cities such as Winnipeg, Edmonton

and Victoria

began as outposts of the Hudson's Bay Company's

fur trade and many small communities across the Canadian North grew up around a

Company post. As settlement increased in the West, the Hudson's

Bay Company became increasingly involved in the retail trade, and by the early

years of the twentieth century sales shops and stores existed in major centers

across Western Canada and in the North. The

first Hudson's Bay Company "department

store" opened in Winnipeg

in 1881, and for years was a major hub of the fur trade. The Hudson's Bay Company and the North West

Company merged in 1821 bringing an end to the fierce competition and strife

that had racked the fur trade in Canada for more than two decades. The merger

secured the Hudson's Bay Company monopoly from Hudson Bay to Lake Athabaska in

Canada, however, the company still faced competition along the international

boundary with the United States. Alexander Ross was the leader of the

Hudson's Bay Company's 1824 trapping expedition into Snake Country. They

traveled from Flathead House, to the mouth of Hell's Gate Canyon, thence south

up the Bitter Root River to a prairie where they were snowbound for a month;

now know as Ross' Hole. From there, they crossed Gibbon Pass into Big Hole,

over to Lemhi valley and then spent the summer trapping streams of central

Idaho.

In 1821 the [North] American Fur Company merged with the Hudson Bay Company.

Their territory in Washington and Oregon was then established.

·

Louis XIII, in Acadia, Nova Scotia, chartered

the Northwest Fur Company in 1630. The

British Government under the Treaty of Utrecht in 1714 recognized its existence

and legality to trap for furs. In 1812 the company discovered that Americans

had “encroached” on land near the British-American border in the west; with the

border not yet clearly established. Under the Canadian auspices, they sent

David Thompson as their agent to the Columbia River. He arrived there on 15

July 1813, and established a trading post at Astoria in an attempt to take

control of the area. On 16 October 1813, the business partners of Hunt &

Astor, who managed the Pacific Fur Company in Astoria, sold out to the

Northwest Fur Company, with all personnel joining them. At this time the name

of Astoria was changed to Fort George. This soon figured prominently in the War

of 1812.

·

The American Fur Company was

chartered by John Jacob Astor in 1808 to compete with the Northwest Fur Company

and the Hudson's Bay Company in Canada.

Additionally he created other companies within this main body to specialize in

certain areas. In 1823 Astor ended this new threat by summoning David Stone and

Oliver Bostwick to New York and buying up their goods and contracts. Then he

hired them, putting Bostwick in charge of his St. Louis operation and Stone in

charge of Detroit. Astor then established the Western

Department of the American Fur Company, his second American Fur Company, at

St. Louis and put Ramsay Crooks in charge. Crooks was a Scot and a fur trader

out of Montreal who had joined the overland Astorians and stayed on with Astor.

In 1824 he established a trading post at Salt Lake. In July 1825, through

Jedediah Smith, established another post near Folsom. In 1825 Crooks married

Bernard Pratte's daughter, Emilie. After Astor retired from the fur trade in

1834, Crooks became president of the company on June 1st, and moved

his family permanently to New York City. Eight years later the American Fur

Company filed for bankruptcy in 1842, it sold its interest in the old Western

Department to Pierre Chouteau, Jr., and Company

of St. Louis. Chouteau's partners were Hercules L. Dousman and Henry H. Sibley,

and the new organization was called the Upper

Mississippi Outfit. The line of demarcation between this outfit and

the American Fur Company's Northern or Fond du Lac Department followed tribal

territory; the former trading with the Sioux and Winnebago, the latter with the

Ojibwe. This operation quickly broke down after the American Fur Company went bankrupt.

·

Articles of incorporation of the Pacific Fur Company were signed in June of 1810,

and were established by John Jacob Astor & Wilson P. Hunt, of New Jersey,

and others, to gain trade from the Columbia River area on the west coast. He

held it until 1834, at which time he sold his interests to some St. Louis

partners. When Astor withdrew in 1834, the company split and the name became

the property of the former northern branch under Ramsey Crooks. Stuart and

Hunt, employed by him from the beginning, established trade routes in 1810-1811

throughout the region and discovered South Pass. The Columbia River location

slightly ahead of their British counterparts. Under Crooks, the company

immediately began to diversify its operations. He maintained two Lake Superior

outfits, one at LaPoint, the other at Sault Ste. Marie under Franchere. At this

time he also moved the inland headquarters of the company form Michilimackinac

to LaPoint on Lake Superior.

The American Fur Company operated under a different system than either the

Hudson's Bay Company or the North West Company. Astor acted as importing and

selling agent for the American Fur Company, which in turn served as liaison to

the traders in the field. Each trader was assigned a department, or

"outfit." The trader normally assumed all risk of profit or loss,

although sometimes the American Fur Company shared in profit or loss on a

fifty-fifty basis.

·

Another operation was centered on the Great

Lakes, and was called the South West Company.

Canadian merchants had a part. The War of 1812 destroyed the firm. In 1817 an

act of Congress excluded foreign traders from U.S. territory, and the American

Fur Company took over the trade in the Lakes region previously held by the

South West Company.

·

Astor made an alliance in 1821 with the Chouteau

interests of St. Louis Missouri Fur Company giving his company a monopoly of

the trade in the Missouri River region and later in the Rocky Mountain regions.

·

Drips and Vanderburgh, operating with the American

Fur Company, followed Bridger and others very closely after 1832, and attempted

to capture all their trade. This severely cut into any profits the firm might

make and led to the eventual dissolution of the American company.

·

“Articles of Association and Co-partnership of

the St. Louis Missouri Fur Company were

made on 7 March 1809, and entered into by and between Benjamin Wilkinson,

Pierre Chouteau senior, Manuel Lisa, Augustin Chouteau junior, Reuben Lewis,

William Clark and Sylvestre Labbadie all of the town of St. Louis and Territory

of Louisiana, and Pierre Menard and William Morrison of the town of Kaskaskia

in the Territory of Indiana, and also Andrew Henry of Louisiana, and also Dennis Fitzhugh of Louisville, Kentucky

for the purposes of trading and hunting up the river Missouri and to the head

waters thereof or at such other place or places as a majority of the

subscribing co-partners may elect.

[In the original manuscript Andrew Henry wasn’t listed, in a revised version he

was.] Jones & Immel were agents for this firm, and later massacred [near

Indian Rock, in Billings.]. John Coulter & Potts were hired to befriend the

Blackfoot, but failed in their endeavor. Potts was killed, Coulter barely

escaped. The War of 1812 essentially stopped all interests in the fur trade,

and it wasn’t until 1818 when Joshua Pilcher took over the management. By 1821

they were re-established on the Yellowstone. There in 1821 they constructed a

trading post called Fort Benton downstream of where Fort Manuel Lisa was

previously established, on the Big Horn River.

·

Article 5th [Article of Association]

And whereas the above named Manuel Lisa, Pierre Menard and William Morrison

were lately associated in a trading expedition up the said River Missouri and

have now a fort established on the waters of the Yellow Stone river, a branch

of the Missouri, at which said fort they have as is alleged by them a quantity

of Merchandise and also a number of horses. Fort Lisa was located at the mouth

of the Big Horn River, and was in operation for only one season. A fort at

Three Forks was established in 1810, but was abandoned.

·

Now therefore it is agreed that this Company is

to accept from them the said Manuel Lisa, Pierre Menard & William Morrison

all the merchandise they may have on hand at the time the first expedition to

be sent up by this Company shall arrive at said fort. Provided however that the

same is not then damaged, and if the same or any part thereof should be damaged

then the company shall only be bound to receive such parts and parcels thereof

as may be fit for trading or such parts as may not be damaged, and for the

whole or such parts thereof as may be received by a majority of the other

members of this company then present this company is to allow and pay them the said

Manuel Lisa, Pierre Menard & William Morrison one hundred per centum of the

first cost. “

·

William Henry Ashley started the Rocky Mountain Fur Company in 1822, and initiated

a series of advertisements for trappers. This is the firm where most of the mountain

men were employed under contracts ranging from one to three years duration.

o

Nathaniel Jarvis Wyeth was interested in the

fur-trade possibilities of the Pacific Northwest and in 1832 he attended the

annual get-together of trappers, traders, and Indians known as the Rendezvous,

established earlier in 1826 by Andrew Henry. While attending he made an

agreement with representatives of the Rocky Mountain Fur Company to bring

$3,000 worth of trade goods for them at the 1834 Rendezvous. This he did, but

the company, being in financial difficulties, refused to accept the goods.

Wyeth, not seeing any other way open to him, moved on westward with the men and

the goods until he reached "The Bottoms" of the Snake River on July

15, 1834. There on the 18th of July he started the construction of a trading

post, which he named Fort Hall in honor of the oldest member of the New England

Company financing his enterprise. On August 4th he finished the log structure.

The next morning, August 5, he raised a homemade United States flag, saluted it

with a salvo of guns, and thus, as the result of a broken agreement, Fort Hall

came into existence, an event whose historical significance can not be

overrated.

·

In an effort to undermine the new competition,

the Hudson Bay Company built Fort Boise near the junction of Boise River and

the Snake. The effort succeeded and Hudson Bay bought out Wyeth in 1837. The

HBC remained in control of the post until it was abandoned in 1855 because of

declining profits and increased Indian hostility.

o

On 18 July 1826 William H. Ashley decided to

separate himself from the fur business, and accordingly agreed to set this

transaction up as a separate operation for three of his former employees commanded

by Jedediah S. Smith, David E. Jackson and Wm. L. Sublette. The partnership was

called “Smith Jackson & Sublett.” The

firm was initially chartered for one year, with options [this charter was

obviously extended, but no written record has yet been located.] All supplies

had to be purchased from the Rocky Mountain Fur Company at pre-agreed upon

prices. All furs obtained were to be sold back to the Ashley’s fur company in

St. Louis.

o

After the Rocky

Mountain Fur Company had extended its business by the purchase of Mr. Ashley's

interest, the partners determined to push their enterprise to the Pacific

coast, regardless of the opposition they were likely to encounter from the

Hudson's Bay traders. Accordingly, in

the spring of 1827, the Company was divided up into three parts, to be led

separately, by different routes, into the Indian Territory, nearer the ocean.

§

One of the routes, commanded by Smith was from the

Platte River, southwards to Santa Fe, then to the bay of San Francisco, and

then north and along the Columbia River.

His party was successful, and had arrived in the autumn of the following

year [1828] at the Umpqua River, about two hundred miles South of the Columbia,

in safety. His party at this time

consisted of thirteen men, with their horses, and a collection of furs valued

at twenty thousand dollars. Here they

were attacked.

§

In August 1830, while at their annual

rendezvous, Bridger, Fitzpatrick, William Sublette, Freaeb and Gervais bought

out Smith’s interests in his partnership, and then they purchased the full

company from Ashley and Henry, retaining the name.

§

A Comanche killed Smith

in 1831; the Rocky Mountain Fur Company continued its operations under the

command of Bridger, Fitzpatrick, and Milton Sublette, brother of William

Sublette. In the spring of 1830, before

Smith sold his interests in the company, they received about two hundred

recruits from the St. Louis area, and with little variation kept up their

number of three or four hundred men for a period of eight or ten years longer,

or until the beaver were hunted out of every nook and corner of the Rocky

Mountains.

o Ashley

initiated a series of Rendezvous, where the furs were collected and then

transported to St. Louis.

This saved both time and money. The sites were located at:

§

1825 - Confluence of Burnt Fork, Henry's Fork,

and Birch Creek, near present-day Burnt Fork, WY.

§

1826 – Mouth of Blacksmith's Fork Canyon, near

present-day Hyrum, Utah

§

1827 – South end of Bear Lake, Utah.

§

1828 – South end of Bear Lake, Utah - Same

location as 1827.

§

1829 – Popo Agie, near Lander, WY

§

1830 – Confluence of Popo-Agie River and Wind

River, near present-day Riverton, Wyoming.

§

1831

– Cache Valley, Utah.

§

1832 – Pierre’s Hole, near Driggs, Idaho.

§

1833 – Green River, confluence of Horse Creek

near Pinedale, Wyoming.

§

1834 – Ham's Fork, SE of present day Kemmerer,

WY; Actually was held at four different sites within ten miles of each other

§

1835 – Green River, confluence of Horse Creek

near Pinedale, Wyoming.

§

1836 – Green River, confluence of Horse Creek

near Pinedale, Wyoming.

§

1837 – Green river, confluence of Horse Creek

near Pinedale, Wyoming.

§

1838 – Confluence of Popo-Agie River and Wind

River, near present-day Riverton, Wyoming.

§

1839 – Green River, confluence of Horse Creek

near Pinedale, Wyoming.

§

1840 – Green River, confluence of Horse Creek

near Pinedale, Wyoming.

Major

Henry’s Expedition – 1823 to 1824 (Yellowstone & Continental Divide)

This was Jim Bridger’s initiation

into the wilderness areas. On August 20th, near the Grand River

north and south fork junctions, the Rees Indians attacked, killing two members

of the train, Anderson and Neil. This was Jim’s first fight. After the fight

the group headed quickly for the Yellowstone River. A large bear attacked and

severely wounded their guide, Hugh Glass, and it certainly appeared that he

would soon die. Jim volunteered to stay with the wounded man; no one else would

do so, but later Thomas Fitzpatrick, a trapper, agreed to stay with him. After

three days, Hugh appeared to be on the verge of death. Fitzgerald saw Indian

signs, became frightened, and convinced Bridger to leave Hugh and escape. They

took Hugh’s personal belongings, leaving the unconscious man without any

protection. The two rushed towards the Yellowstone and met up with the Henry

Train. There they were under almost constant attack from the Assiniboine,

Blackfoot and Gros Ventres. Henry’s train made a dash for the mouth of the Big

Horn River. On the way, they met some friendly Crow Indians, and traded them

out of 47 horses. At the Big Horn the group split, with Bridger and Etienne

Provost heading up to the Powder River, and then to the Sweetwater and finally

across the Continental Divide to trap beaver. When winter arrived they traveled

back to the Big Horn, in January 1824. While at this trapper camp, Hugh Glass

appeared, grabbed Bridger and said, “Speak up, young-un, quick – afore I kill

you.” Fortunately for Jim, at that very moment other trappers appeared and took

Hugh’s mind off of Jim. Major Henry appeared, demanding to know what the fuss

was about, and learning of the shame had Glass and Bridger brought into his

cabin. Fitzgerald had departed some time earlier. Hugh blamed Fitzgerald, and

not Jim; but Jim would always carry his shame. After this encounter, Jim always

looked out for his fellow men, so much so that he was given the name “Old

Gabe.”

“For more than two years Bridger had been a freeman working for Sublette’s firm

with increasing leadership responsibilities, in effect acting as a lieutenant

for the Captain, and participating in the planning, recommending places to hunt

and trap and relaying orders to the men. Apparently Jedediah Smith's

familiarity with the Bible and its references to the Angel Gabriel's duty to

reveal Jehovah's caused him to see in Bridger some similarity to "Old

Gabriel". He began referring to Bridger in this manner and soon he became

"Old Gabe" to most of those in camp and to many others as time went

on although only twenty-six years old. The Flatheads and Crows also knew him as

“Blanket Chief” after his Flathead wife made a beautiful and unusual

multicolored blanket that he wore and had for special occasions. The name meant

little at first but as he became known for the qualities the Indians admired,

the name became greatly respected and honored.”

Details of the expeditions and

when each event occurred are explained in the Discovery of South Pass, below

and in Part 2 of this glossary.

Discovery of South Pass – Trail to Continental Divide 1824 - 1825

"Most emigrants have a very erroneous idea of South Pass, and their

inquiries about it are amusing enough. They suppose it to be a narrow defile in

the Rocky Mountains walled by perpendicular rocks hundreds of feet high. The

fact is the pass is a valley some 20 miles wide."

In 1812 Robert

Stuart and six companions correctly located the mountain pass when they

returned east to solicit help from their sponsor, Jacob Astor.

Stuart wasn't sure where he

had been and ten more years would pass before another party of explorers would

re-discover the pass he had found. This pass would be critical to emigrants who

went to the Oregon Territory.

The South Pass is

located at the south end of the Wind River Mountain range and river, at the

junction of Wyoming and Oregon. In 1848 the southwestern portion of the U. S.

[Utah, California, Nevada, and portions of Wyoming, Arizona, New Mexico and

Colorado, which belonged to Mexico], were ceded to the United Sates. Various

persons have been given credit for discovery of the pass. Oregon belonged to

the British until 1846.

“Mr. David Stuart sailed

from this port on September 10, 1810 for

the Columbia River on board the ship 'Tonquin' with a number of Mr. Astor's

associates in the 'Pacific Fur Company,' arriving on the Columbia River 24

March, 1811.

After the breaking up of the company in 1814, he returned through the Northwest

Company's territories to Montreal, far to the north of the 'South Pass,' which

he never saw.

In

1811, the overland party of Mr. Astor's expedition, under the command of Mr.

Wilson P. Hunt, of Trenton, New Jersey, although numbering sixty well armed

men, found the Indians so very troublesome in the country of the Yellowstone

River, that the party of seven persons who left Astoria toward the end of June,

1812, considering it dangerous to pass again by the route of 1811, turned

toward the southeast as soon as they had crossed the main chain of the Rocky

Mountains, and, after several days' journey, came through the celebrated 'South

Pass' in the month of November, 1812.

·

Pursuing from thence an easterly course, they

fell upon the River Platte of the Missouri, where they passed the winter and

reached St. Louis in April 1813.

·

The seven persons forming the party were

Robert McClelland of Hagerstown, who, with the celebrated Captain Wells, was

captain of spies under General Wayne in his famous Indian campaign, Joseph

Miller of Baltimore, for several years an officer of the U. S. army, Robert

Stuart, a citizen of Detroit, Benjamin Jones, of Missouri, who acted as

huntsman of the party, Francois LeClaire, a half-breed, and Adré Valée, a

Canadian voyageur, and Ramsay Crooks, who is the only survivor of this small

band of adventurers.”

·

ON the eighth of September 1810, the Tonquin

put to sea, where the frigate Constitution soon joined her. The wind was fresh

and fair from the southwest, and the ship was soon out of sight of land and

free from the apprehended danger of interruption. The frigate, therefore, gave her

"God speed," and left her to her course.

·

William Price Hunt used the information supplied by the Lewis

and Clark expedition to lead the overland trappers to Fort Astoria. They

reached the mouth of the Columbia River in February of 1812 where the seafaring

group that had arrived months earlier, in 1811 had already erected the fort

“Astoria”. After the fort was lost in 1812, an overland expedition headed by

Robert Stuart was established. This group established the major portions of the

Oregon Trail by finding the South Pass through the Rocky Mountains, a

route that had earlier eluded both the Lewis and Clark expedition and the Hunt

exploration.

·

In 1812 a secret agent at the fort

treacherously sold it to the North West Company, and shortly after, the English,

then at war with the United States, took military possession. In 1818 the fort

was formally surrendered to the United States, but the North West Company

remained in the actual occupation of the country. Its only rival now was the

Hudson's Bay Company. For a time these two companies maintained a bloody feud,

till finally, in 1821, they amalgamated into one trading company under the

valuable franchises of the Hudson's Bay Company. The new company has now drawn

to itself all the trade on the Columbia and has actually expelled the United

States from this part of its territory.

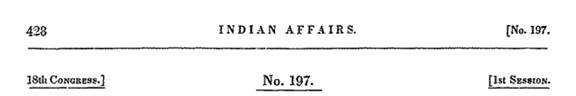

Ashley’s 1st

Expedition

This

advertisement appeared in the Missouri Republican starting on 20 March 1822,

“The subscriber wishes to engage one hundred young men to ascend the Missouri

River to its source, there to be employed for one, two, or three years. For

particulars inquire of Major Andrew Henry, near the lead mines of Washington,

who will ascend with, and command of, the party; or of the subscriber near St.

Louis. William H. Ashley.” In February of 1822, Ashley placed a

similar advertisement in the St Louis Missouri Gazette & Public Advertiser

which stated: “TO Enterprising Young Men

The subscriber wishes to engage ONE HUNDRED MEN, to ascend the river Missouri

to its source, there to be employed for one, two or three years. — For

particulars enquire of Major Andrew Henry, near the Lead Mines, in the County

of Washington, (who will ascend with, and command the party) or to the

subscriber at St. Louis. Wm. H. Ashley”

Other ads appeared in various papers, but the wording was

about the same.

Ashley sent fur-trading expeditions up the Missouri River to

the Yellowstone in 1822(1st) and 1823(2nd). A detachment

of the 2nd commanded by Thomas Fitzpatrick went through South Pass

to the Green River valley. In 1824(3rd) Ashley accompanied another

expedition that crossed from the upper Platte to Green River and began its

exploration. Another followed this in 1824 and again in 1825. In the Green

River valley he held the first rendezvous of the mountain fur traders and

trappers. In 1826 he led his final expedition that reached the vicinity of

Great Salt Lake. Having acquired an ample fortune, he retired from the fur

trade.

Ashley loaded $20,000 worth of

supplies into two keelboats belonging to the American Fur Company, and a small

detachment of men would man these. A few others were assigned to ride horses

and guide 60 packhorses that would be needed later. They were to accompany the

river travelers on the journey as near to the riverbanks as practical. There

were 150 men to start with. Jim Bridger was in the lead boat with Major Henry

and Mike Fink. Fink was considered to be “King of the Keelboat Men.” Col Ashley

commanded the second boat. The boats were manned by six-oarsmen, and twenty

pole-men. They departed St. Louis in April 1822. After reaching a point on the

Missouri River near Fort Osage, the 2nd boat capsized, it and the

cargo was lost; but his men were

rescued. Ashley

immediately returned to St. Louis and started building a supply expedition for

the men now stationed on the Yellowstone at Fort Henry. For this action

Jedediah Smith and a few others accompanied Ashley downriver to St. Louis. A

third boat carrying supplies, and commanded by Col. Ashley, made it to the

stranded men on the Yellowstone where Fort Henry was founded. Ashley and Smith

returned to St. Louis by the same boat before winter set in. John Weber,

age 43, soon after arriving at the Yellowstone in 1822, was placed in charge of

a party to explore and trap the Yellowstone and the Powder Rivers. In this his

first journey up river, Weber had to learn to deal carefully with the Sioux,

the Arikara, the Blackfeet, and the Mandans, and would soon encounter the

Crows, the Snakes, and the Gros Ventres. Weber then spent much of 1823 with his

party on the Yellowstone, and by that fall, Ashley had outfitted Weber’s party

with horses for a winter of trapping and trading. They trapped the Big Horn

Basin and probably spent the winter of 1823-24 in the Wind River Valley (near

present-day Dubois)

with Jedediah Smith’s party and Crow Indians.

NOTE: Refer to “Atkinson-O-Fallon

Expedition of 1825” for another view about the Arikara Indians and their

Activities, trading

& battles with the Missouri Fur Company.

Daniel

Potts Letter: “I

took my departure [from Illinois] for Missouri, from thence immediately entered

on an expedition of Henry and Ashly, bound for the Rocky Mountain and Columbia

River. In this enterprize I consider it unnecessary to give you all the

particulars appertaining to my travell I left St. Louis on April 3d, 1822,

under command of Andrew Henry with a boat and one hundred men and arrived at

Council Bluffs on May 1st; from thence we ascended the river to Cedar Fort,

about five hundred miles. Here our provisions being exhausted, and no prospect

of game near at hand, I concluded to make the best of my way back in company

with eight others, and unfortunately was separated from them. By being too

accessary in this misfortune, I was left in the Prarie without arms or any

means of making fire, and half starved to death. Now taking into consideration

my situation, about three hundred and fifty miles from my frontier Post, this

would make the most cruel heart sympathise for me. The same day I met with

three Indians, whom I hailed, and on my advancing they prepared for action by

presenting their arms, though I approached them without hesitation, and gave

them my hand. They conducted me to their village, where I was treated with the

greatest humanity imaginable. There I remained four days, during which time

they had many religious ceremonies too tedious to insert, after which I met

with some traders who conducted me as far down as the ? Village - this being

two hundred miles from the Post. I departed alone as before, with only about

1/4 lb. suet, and in six days reached the Post where I met with Gen. Ashley, on

a second expedition, with whom I entered for the second time, and arrived at

the mouth of Yellow Stone about the middle of October. This is one of the most

beautiful situations I ever saw; from this I immediately embarked for the mouth

of Muscle Shell, in company with twenty one others and shortly after our

arrival, eight men returned to the former place. Here the game being very

scarce, the prospect was very discouraging, though after a short time the

Buffaloes flocked in in great abundance; likewise the Mountain Goats; the like

I have never seen since.”

The Arikara Indians took the cargo from Ashley’s fourth

boat, initiating an immediate dislike between the two groups. This meant that

half of the team would be marching overland to the Great Falls of the Missouri

[headwaters.] Col Ashley now took command of the horses and ground party.

Assiniboines attacked the ground party after reaching the Grand River [above

the Cheyenne] and the Indians stole all of the loose horses, which were to

carry their packs to the headwaters. The group continued on to the junction

with the Yellowstone River, and then made a change in plans. Here they would

spend the winter, then start out west for the Three-Forks area near the Great

Falls. [At this river junction these is no evidence of any mountains, and the

new-young trappers felt cheated.] In the spring of 1823, the group split up and

headed for the headwaters, some by boat, others afoot. After the Henry group

reached Great Falls they were attacked by Blackfeet and had to retreat. At this

same time, reports of the Blackfeet

massacre of Jones and Immel, on the Yellowstone

reached them by messenger. Immediately afterward two men arrived from Col Ashley’s

command of his 2nd Expedition, located some 200 miles south at the Arikara

village. One was a

French-Canadian the other Jedediah Smith. They reported that 800 Indians near

the Ree villages attacked them, thirteen were killed, and a dozen more wounded,

and all stock was stolen.

Henry’s men were asked to get downriver to them as quickly as possible. Major

Henry split up his command, leaving only a few to look after their supplies.

Jim Bridger was among the eighty selected to go. They met up with Col Ashley’s

men the following month in the first week of July.

Various listings of personnel who started out on the 1st

Expedition have been developed over the years, and none of them seem to agree on

the participants; due in part to the mixing-up of the members who traveled on

the 2nd and 3rd Expeditions, and the confusion with the

travel dates and apparent errors on when the 1st Expedition started.

Mainly the various diary extracts and the significant events have been

inter-mixed without regard to the specific expedition journey. Most all of

these persons remained with Ashley & Henry during the first three

Expeditions. In the listing for the 1st Expedition were:

Col. Ashley, Major Henry, Sublette, Tom Fitzpatrick, Hugh

Glass, Edward Rose, Jim Beckwourth, Talbot, Carpenter, David Jackson, Robert

Campbell, Etienne Provost, James Bridger,

John H. Weber, Jedediah

Smith, David E. Jackson and Mike Fink.

Note: James P. Beckwourth was born a slave

on a Virginia plantation, and rose in fame to become one of the most successful

man in the history of the west, as well as one of the most successful trader

for the Rocky mountain Fur Company. He established a Trading Post in Colorado,

which later became Pueblo. He had a large ranch, and married more women than

most any other man, many at the same time. He led many military expeditions and

rose to become “Black Chief” of the Crow Tribe. He was employed as a slave to

the McGinn Blacksmith shop in St. Joseph, Missouri when Ashley recruited men

for his first trip. McGinn lent him $300 to buy his freedom, so that he might

join the group. Soon as he could the money was repaid, and he went on to become

a man of great fame.

Ashley’s plan for his 2nd

Expedition was to reach the beaver-rich land west of the Rockies in the valley

of the Spanish River, or Rio Colorado [Green River in the southwestern part of

Wyoming.] Problems with Indian tribes forced Ashley to change his 1st

Expedition plan of reaching this area via the Missouri, Yellowstone and Bighorn

Rivers. He elected instead to send a party of men overland, directly west to

Crow Country, across the continental divide and on to Spanish River. [Edward

Rose was previously employed by Manuel Lisa, and had lived with the Crow

Indians, had knowledge of the region and had previously made this same trip.]

Ashley for his 3rd Expedition wanted his

men to locate an easy pass to the hunting grounds over the Continental Divide. Ashley

chose from eleven to sixteen or seventeen men. Jedediah Smith captained this

group, and among the followers were Thomas Fitzpatrick [second in command],

William Sublette, James Clyman, Thomas Eddie, Edward Rose, Stone and Branch. Names of the others weren’t recorded. In the fall of 1823, Smith led his small

company of men in search of new beaver territory. In September 1823, they left

the Missouri River at Fort Kiowa and pushed west across South Dakota heading

for the Yellowstone River.

Ashley’s 2nd Expedition – 1823

William Ashley ran a repeat

advertisement in the St. Louis Gazette and Public Advertiser in the

winter of 1822: "Enterprising Young Men...to ascend the Missouri to its

source, there to be employed for one, two, or three years."

This trip was to continue with his plan to reach the headwaters of the

Missouri, and join up with his partner. Joining him at this time was Henry

Clyman.

When

winter was over and the river cleared, Ashley left in April 1823. After almost

two months journey they arrived at an Arikara Indian village, located on

the Missouri about 200 miles south of where Henry’s group of trappers were

located, he stopped and met with the chiefs and traded goods, including guns

and whiskey. Things were fine until one of his men decided

to visit the village in the middle of the night and was killed. On June 2,

after that episode, the group was attacked by Arikara Indians, their supplies

stolen, and they were forced to retreat.

Ashley lost fifteen men before withdrawing back down the river. He sent

Jedediah Smith and a guide upriver to Henry’s location with a request for help

and another group of men downstream to Fort Atkinson for military help.

Comment: According to

the Diary of Clyman, that the event took place in 1824, and that more than one

member of the Ashley Expedition snuck into the village. “In the night of the

third day Several of our men without permition went and remained in the village

amongst them our Interpreter Mr. Rose about midnight he came running into

camp & informed us that one of our men was killed in the village and war

was declared in earnest We had no Military organization diciplin or

Subordination Several advised to cross over the river at once but

thought best to wait untill day light But Gnl. Ashley our imployer Thought best

to wait till morning and go into the village and demand the body of our comrade

and his Murderer Ashley being the most interested his advice

prevailed We laid on our arms epecting an attact as their was

a continual Hubbub in the village“

“The

military responded as well as fifty

men in canoes from Fort Henry; plus a large group of Sioux Indians, enemies of

the Arikaras came along. Gen. Leavenworth was in charge of the forces and the

Indian Agent, Pilcher, accompanied him. This incident suddenly had the

attention of the whole eastern U.S., as this was the first military action

taken against the Indians of west of the Mississippi. Ashley only wanted the

merchandise that had been stolen from his party and a promise that the Arikaras

would not attack again. After an initial attack by the Sioux, the Arikaras were

willing to talk about peace. Leavenworth and Ashley met with the Indian chiefs,

made peace, gained the return of Ashley's goods and horses and a promise by the

Arikaras not to attack again. Pilcher refused to smoke the peace pipe and did

not want to be part of the deal. Later, as the agreement was being effected,

Pilcher and his men burned the villages. Pilcher and his men were given

dishonorable discharges from the group while Ashley and his men received

honorable discharges.”

“After

Major Henry joined them and the troops from Council Bluffs, under command of

Col Levengworth, they gave them battle; the loss of our enemy was from sixty to

seventy. The number of the wounded not known, as they evacuated their village

in the night. On our part there was only two wounded, but on his return he was

fired upon by night by a party of Mannans wherein two was killed and as many

wounded. Only two of our guns were fired which dispatched an Indian and they

retreated. Shortly after his arrival we embarked for the big Horn on the Yellow

Stone in the Crow Indian country, here I made a small hunt for Beaver. From

this place we crossed the first range of Rocky Mountain into a large and

beautiful valley adorned with many flowers and interspersed with many useful

herbs. At the upper end of this valley on the Horn is the most beautiful scene

of nature I have ever seen. It is a large boiling spring at the foot of a small

burnt mountain about two rods in diameter and depth not ascertained,

discharging sufficient water for an overshot mill, and spreading itself to a

considerable width forming a great number of basons of various shapes and

sizes, of incrustation of sediment, running in this, manner for the space of

200 feet, there falling over a precipice of about 30 feet perpendicular into

the head of the horn or confluence of Wind River. From thence across the 2d

range of mountains to Wind River Valley. In crossing this mountain I

unfortunately froze my feet and was unable to travel from the loss of two toes.

Here I am obliged to remark the humanity of the natives (the Indians) towards

me, who conducted me to their village, into the lodge of their Chief, who

regularly twice a day divested himself of all his clothing except his breech

clout, and dressed my wounds, until I left them. Wind River is a beautiful

transparent stream, with hard gravel bottom about 70 or 80 yards wide, rising

in the main range of Rocky Mountains, running E.N.E, finally north through a

picteresque small mountain bearing the name of the stream: after it discharges

through this mountain it loses its name. The valleys near the head of this

river and its tributary streams are tolerably timbered with cotton wood,

willow, &c. The grass and herbage are good and plenty, of all the varieties

common to this country. In this valley the snow rarely falls more than three to

four inches deep and never remains more than three or four days, although it is

surrounded by stupendous mountains. Those on S. W. and N. are covered with

eternal snow. The mildness of the winter in this valley may readily be imputed

to the immense number of Hot Springs which rise near the head of the river. I

visited but one of those which rise to the south of the river in a level plain

of prairie, and occupies about two acres; this is not so hot as many others but

I suppose to be boiling as the outer verge was nearly scalding hot. There is

also an Oil Spring in this valley, which discharges 60 or 70 gallons of pure

oil per day. The oil has very much the appearance, taste and smell of British

Oil. From this valley we proceeded by S. W. direction over a tolerable route to

the heads of Sweet Water, a small stream which takes an eastern course and

falls into the north fork of the Great Platt, 70 or 80 miles below. This stream

rises and runs on the highest ground in all this country. The winters are

extremely, and even the summers are disagreeably cold”

In addition, after joining up at the battle site, the two

partners, Ashley and Henry, went to the Teton River where they purchased Indian

ponies from the Sioux. They now had means of transportation that wasn’t limited

to a fixed location and abandoned the use of rivers as their main method of

travel. After arriving at the battle site, Henry’s group learned that the

military under the command of Colonel Henry Leavenworth sent three keelboats of

supplies, artillery, and six companies of soldiers from the Sixth Infantry,

accounting for about 800 men. Joining this force were all available resources

of the Missouri Fur Company, commanded by Joshua Pilcher plus about 500 Sioux

warriors under Chief Fireheart. Along the way one boat was sunk with its

supplies and 70 muskets. The fur company replaced their muskets with their

rifles. This action prompted Leavenworth to organize the fur company’s forces

as the “Missouri Legion.” He then commissioned several of the mountain men as

members of this command:

·

Jed Smith – Captain Edward

Rose – Ensign Thomas

Fitzpatrick – Quartermaster

·

William Sublette – Sergeant Major Henry Vanderburgh – Captain Angus

McDonald – Captain

·

Moss B. Carson – 1st Lt William Gordon – 2nd Lt Jim Bridger – Buck Private

·

Unknown – Buck Private

Major Henry conceived an idea the following year of

having their trappers get pelts and meet at some selected rendezvous once each

year, much like Manuel Lisa had, to collect their bounties, and then return the

furs to St. Louis. The group led by Col Ashley followed the Platte as far as

the Green River. Here they established a

trading post [Fort Henry] in Wyoming near to its mouth on the Missouri.

Trappers made trips through the country on this side of the Rocky Mountains to

the Green River. Beaver trapping promised most profit. From this post arose

leaders for subsequent enterprises, such as Smith, Fitzpatrick, Bridger, Robert

Campbell, and William Sublette, names well known to every mountaineer.

Jim Bridger remained with the firm, learning all he could about trapping and

the land, until spring of 1825 [probably about April, 1825.]

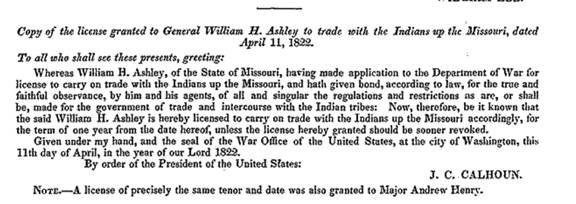

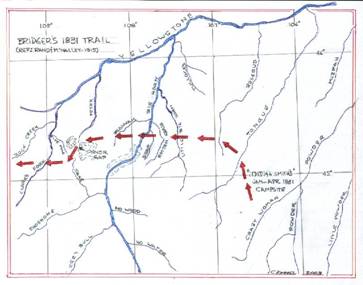

Area map from Stanley Vestal I

Ashley’s 3rd

Expedition - 1824

“In 1824, Mr.

Ashley repeated his earlier expedition, extending it this time beyond Green River

as far as Great Salt Lake. South of there he discovered a smaller lake, which

he named Lake Ashley, after himself. On the shores of this lake he built a fort

for trading with the Indians, and leaving in it about one hundred men, returned

to St. Louis the second time with a large amount of furs. During the time the

fort was occupied by Mr. Ashley's men, a period of three years, more than one

hundred and eighty thousand dollars worth of furs were collected and sent to

St. Louis. In 1827, the fort, and all

Mr. Ashley's interest in the business, was sold to the Rocky Mountain Fur

Company, owned by Jedediah Smith, William Sublette, and David Jackson; Sublette

being the leader of the Company. . Following up the Platte River, Mr. Ashley

proceeded at the head of a large party with horses and merchandise, as far as

the northern branch of the Platte, called the Sweetwater. This he explored to its source, situated in

that remarkable depression in the Rocky Mountains, known as the South Pass .”

According to the original diary

of James Clyman he states that the Ashley Expedition left in March 1824.

His remarks are somewhat rambling, but the following excerpts identify where

the Ashley Expedition traveled. After the 15th of June 1824 portions of the expedition got

separated, and carrying their beaver pelts, the separated groups, including

Fitzpatrick, made their way to Fort Leavenworth.

According to the original diary

of James Clyman he states that the Ashley Expedition left in March 1824.

His remarks are somewhat rambling, but the following excerpts identify where

the Ashley Expedition traveled. After the 15th of June 1824 portions of the expedition got

separated, and carrying their beaver pelts, the separated groups, including

Fitzpatrick, made their way to Fort Leavenworth.

Born in Virginia, Clyman

stated in his published book that he, along with many others had first joined William

H. Ashley’s 2nd Expedition to the West in 1823,

and was reported to be one of the first to cross over South Pass. He explored

the region around the Great Salt Lake (Lake Bonneville) with William Sublette.

In 1844 he went to Oregon, then down into California the following year,

returned east with Caleb Greenwood via the Hastings Cutoff (warning westbound

travelers, including the Donner Party, not to take that trail.) Catching gold

fever he returned again to California in 1848.

"On the 8th of March 1824 all things ready we shoved off from the

shore [St. Louis] fired a swivel which was answered by a Shout from the shore

which we returned with a will and porceed up stream under sail

"A discription of our crew I cannt give

but Fallstafs Battallion was genteel in comparison I think we

had about (70) seventy all told Two Keel Boats with crews of

French some St Louis gumboes as they were called

"We proceeded slowly up the Misouri

River under sail wen winds ware favourable and towline when not

Towing or what was then calld cordell is a slow and tedious method

of assending swift waters It is done by the men walking on the shore

and hawling the Boat by a long cord Nothing of importance came under

view for some months except loosing men who left us from time to time &

engaging a few new men of a much better appearance than those we

lost The Missourie is a monotinous crooked stream with large

cottonwood forest trees on one side and small young groth on the other with a

bare Sand Barr intervening I will state one circumstance only which

will show something of the character of Missourie Boats men

"We having to hunt for our living we

soon fell behind the Col. and his corps droping down to a place called fort

Keawa a trading establishment blonging to Missourie furr Company

"Here a small company of I think (13)

men ware furnished a few horses onley enough to pack their baggage they going

back to the mouth of the yellow Stone on their way up they ware actacted

in the night by a small party of Rees killing two of thier men and they killing

one Ree amongst this party was a Mr Hugh Glass who could not

be rstrand and kept under Subordination he went off of the

line of march one afternoon and met with a large grissly Bear which he shot at

and wounded the bear as is usual attacted Glass

he attemptd to climb a tree but the bear caught him and hauled to

the ground tearing and lacerating his body in feareful rate

by this time several men ware in close gun shot but could not shoot for fear of

hitting Glass at length the beare appeaed to be satisfied

and turned to leave when 2 or 3 men fired the bear turned

immediately on glass and give him a second mutilation on

turning again several more men shot him when for the third time he pouncd on

Glass and fell dead over his body this I have from

information not being present here I leave Glass for the

presen we having bought a few horses and borrowed a few more

left about the last of September and proceded westward over a dry roling

highland a Elleven in number I must now mention honorable

exceptions to the character of the men engaged at St Louis being now thined

down to onley nine of those who left in March and first Jededdiah Smith who was

our Captain Thomas Fitzpatrick William L. Sublett and Thomas Eddie all of which

will figure more or less in the future

Comment: The bear attack

upon Hugh Glass is reported to have taken place at Shadehill, South Dakota

in 1823, not 1824. All reports, other than Clyman’s diary provide this 1823

date. In Clyman’s Autobiography he states the date was 1823. The difference

hasn’t been explained. His legendary 200-mile trip to Fort Kiowa, near

present-day Chamberlain, is related on a historic marker near the site of his

attack

Jim Bridger and Thomas Fitzpatrick agreed to stay behind and watch Hugh until

he died. “Several

days passed, and with Hugh stll clinging to life, Fitzgerald and Bridger, no

doubt in fear of being found by roving bands of hostile Indians who had battled

the trappers all season, packed up Hugh’s rifle, knife, and other equipment and

hurried on after Henry’s men. They reported that Glass was dead and buried,

showing his possessions as proof. Hugh didn’t die but crawled to safety. Weeks

later he found Jim Bridger at Andrew Henry’s recently established fur trading

post on the Yellowstone River near the mouth of the Big Horn. He did not kill

Bridger, as he must have sworn to do during his long crawl, but instead

reportedly excused Bridger because of his youth, and left him to answer to his

own conscience and to his own God. Hugh did not find Fitzgerald until some time

later, discovering that he had enlisted in the army at Fort Atkinson, near

present Omaha, Nebraska. Hugh likewise did not kill Fitzgerald, perhaps mainly

because the killing of a U.S. soldier carried severe consequences. At any rate,

he also left Fitzgerald to answer to a higher authority, at last recovered his

stolen weapons, and resumed his career as a free trapper and hunter.”

This means that Bridger stayed with the 1st Ashley Expedition on the

Yellowstone through the following year before heading south and joining up with

the 2nd Expedition that went to Green River.

According to Hiram Chittenden in the ‘American Fur Trade of

the Far West’ (pg 953) he states that Fort Kiowa is on the right bank of the

Missouri, about ten miles from where Chamberlain, SD is now located. Earlier,

on page 701 he states that Glass was abandoned about 100 miles from Fort Kiowa.

However, the mouth of the Grand River is 200 miles from the fort, and it is

reported that Glass was wounded near the forks of the Grand River, five day’s

march above the mouth. If Glass crawled in a straight line he would meet the

Missouri River at the mouth of the Cheyenne River.

"Country nearly the same short grass

and plenty of cactus untill we crossed the Chienne River a few miles below

whare it leaves the Black Hill range of Mountains here some

aluvial lands look like they might bear cultivation we did

not keep near enough to the hills for a rout to travel on and again fell into a

tract of county whare no vegetation of any kind existed beeing worn into knobs

and gullies and extremely uneven a loose grayish

coloured soil verry soluble in water running thick as it could move of a pale

whitish coular and remarkably adhesive there on a misty rain

while we were in this pile of ashes and it loded down our horses feet (feet) in

great lumps it looked a little remarkable that not a foot of

level land could be found the narrow revines going in all manner of directions

and the cobble mound of a regular taper from top to bottom

all of them of the percise same angle and the tops share the

whole of this region is moveing to the Misourie River as fast as rain and thawing

of Snow can carry it by enclining a little to the west in a

few hours we got on to smoothe ground and soon cleared ourselves of mud

at length we arived at the foot of the black Hills which rises in

verry slight elevation about the common plain we entered a

pleasant undulating pine Region cool and refreshing so different from the hot

dusty planes we have been so long passing over and here we found hazlenuts and

ripe plumbs a luxury not expected

“The Crow Indians being our place of

destination a half Breed by the name of Rose who spoke the crow tongue was

dispached ahead to find the Crows and try to induce some of them to come to our

assistance we to travel directly west as near as circumstances would

permit supposing we ware on the waters of Powder River we

ought to be within the bounds of the Crow country

continueing five days travel since leaveing our given out horses and likewise

Since Rose left us late in the afternoon while passing through a Brushy bottom

a large Grssely came down the vally we being in single file men on foot leding

pack horses he struck us about the center then turning ran

paralel to our line Capt. Smith being in the advanc he ran

to the open ground and as he immerged from the thicket he and the bear met face

to face Grissly did not hesitate a moment but sprung on the

capt taking him by the head first pitcing sprawling on the

earth he gave him a grab by the middle fortunately cathing by the ball pouch

and Butcher Kife which he broke but breaking several of his ribs and cutting

his head badly none of us having any sugical Knowledge what

was to be done one Said come take hold and he wuld say why not you so it went

around I asked Capt what was best he said

one or 2 for water and if you have a needle and thread git it out and sew up my

wounds around my head which was bleeding freely I got a pair

of scissors and cut off his hair and then began my first Job of dessing

wounds upon examination I the bear had taken nearly all his

head in his capcious mouth close to his left eye on one side and clos to his

right ear on the other and laid the skull bare to near the crown of the head

leaving a white streak whare his teeth passed one of his

ears was torn from his head out to the outer rim after

stitching all the other wounds in the best way I was capabl and according to

the captains directions the ear being the last I told him I could do nothing

for his Eare 0 you must try to stich up some way or other

said he then I put in my needle stiching it through and

through and over and over laying the lacerated parts togather as nice as I

could with my hands water was found in about ame mille when

we all moved down and encamped the captain being able to mount his horse and

ride to camp whare we pitched a tent the onley one we had and made him as

comfortable as circumtances would permit this gave us a

lisson on the charcter of the grissly Baare which we did not forget

I now a found time to ride around

and explore the immediate surroundings of our camp and assertained that we ware

still on the waters of shiann river which heads almost in the eastern part of

the Black hill range taking a western course for a long distance into an uneven

vally whare a large portion of (of) the waters are sunk or absorbd then turning

short to the east it enters the Black hill rang though a narrow Kenyon in

appeareantly the highest and most abrupt part of the mountain enclosed in

immence cliffs of the most pure and Beautifull black smooth and shining and

perhaps five hunded to one thousand feet high

“A mountaneer named Harris being St Louis

some yers after undertook to describe some of the strange things seen in the

mountains saying a petrified forest was lately dicovered

whare the trees branches leaves and all were perfect and the small birds

sitting on them with their mouths open singing at the time of their

transformation to stone

"And landed under the side of an Isle

and two men ware sent up to the mouth of the yellowstone and one boat containing

the wounded and discouraged was sent down to Council bluffs with orders to

continue to St Louis This being the fore part of June

here we lay for Six weeks or two months living on scant and

frquentle no rations allthough game was plenty on the main Shore

perhaps it was my fault in greate measure for several of us being

allowed to go on Shore we ware luckey enough to get Several

Elk each one packing meat to his utmost capacity there came on

a brisk shower of rain Just before we reached the main shore and a brisk wind

arising the men on the (men on the) boat would not bring the skiff and take us

on board the bank being bear and no timber neare we ware

suffering with wet and cold I went off to the nearest timber

made a fire dried and warmed myself laid down and went to sleep

in the morning looking around I saw a fine Buck in easy gun shot

and I suceeded in Killing him then I was in town

plenty of wood plenty of water and plenty of nice fat venison

nothing to do but cook and eat here I remained

untill next morning then taking a good back load to the landing whare I met

several men who had Just landed for the purpose of hunting for me

after this I was scarcely ever allowed to go ashore for I might

never return

"In proceess of time news came that

Col. Livenworth with Seven or eight hundred Sioux Indians ware on the rout to

Punnish the Arrickarees and (18) or (20) men came down from the Yellow Stone

who had gone up the year prevous these men came in Canoes

(came in canoes) and passed the Arrickarees in the night we

ware now landed on the main Shore and allowed more liberty than hertofore

(at) Col. Levenworth about (150) men the remnant of the (6)

Regiment came and Shortly after Major Pilcher with the Sioux Indians (Indians)

amounting to 5 or 600 warriers and (18) or 20 engagies of the Missourie furr

Company and a grand feast was held and speeches made by whites and Indians

"After 2 days talk a feast and an

Indian dance we proceded up stream Some time toward the last

of August we came near the arrickaree villages again a halt

was made arms examined amunition distributed and badges given to our friends

the Sioux which consisted of a strip of white muslin bound around the head to

distinguish friends from foes

”as winter was rapidly approaching we

began to make easy travel west ward and Struck the trail of Shian

Indians the next day we came to their village traded and swaped a

few horses with them and continued our march across a Ridge mountains not steep

& rocky (in general) but smooth and grassy in general with numerous springs

and brook of pure water and well stocked with game dsending

this ridge we came to the waters of Powder River Running West and north

country mountainous and some what rockey

“we ware there through the month of

November [1824] the nights war frosty but the days ware

generally warm and pleasant on Tongue river we struck the

trail of the (of the) Crow Indians Passed over another ridge

of mountains we came on to Wind River which is merely

another name for the Big horn above the Big horn Mountain

the most of this Region is barren and worthless if my recollection is

right from the heads of the Shian untill we came on to Wind

river we ware Bountifully supplied with game but here we found none at

all

“in February we made an effort to cross

the mountains north of the wind River nge but found the snow too deep and had

to return and take a Southern course east of the wind river range which is here

the main Rockey mountans and the main dividing ridge betwen the Atlantic and

Pacific

“in February [1825] we made an effort to

cross the mountains north of the wind River nge but found the snow too deep and

had to return and take a Southern course east of the wind river range which is

here the main Rockey mountans and the main dividing ridge betwen the Atlantic

and Pacific

"In traveling up the Popo Azia a

tributary of Wind River we came to an oil springe neare the main Stream whose

surface was completely covered over with oil resembling Brittish oil and not

far from the same place ware stacks Petrolium of considerable bulk

Buffaloe being scarce our supply of food was Quite scanty

Mr Sublett and my self mounted our horses one morning and put in

quest of game we rode on utill near sundown when we came in sight of three male

bufalo in a verry open and exposed place

“15th of June no sight of Smith or his

party remaining here a few days Fitzpatrick & myself

mounted & fowling down stream some 15 miles we concluded the stream was

unnagable it beeing generally broad & Shallow and all our baggae would have

to be packed to some navigable point below where I would be found waiting my

comrades who would not be more than three or four days in the rear

I moved slowly down stream three days to the mouth where it enters

the North Platt Sweetwater is generafly bare of all kind of

timber but here near the mouth grew a small thick clump of willoes

In

the spring of 1824, some Crow Indians met with Fitzpatrick

and stated “if the white men wanted beaver, they only had to follow a plain

Indian trail to South Pass. Beyond that pass you can throw your traps away and

kill all the beaver you want with clubs.”

According to the Sweetwater

County Joint Travel & Tourism Board, it was actually Captain Smith, who was

commanding the fur trappers who were camped at that time (1824), near

the present town of Dubois, Wyoming, who received this information. Fitzpatrick

was a member of the group. The fur party wintered in 1823 with Crow Indians,

then crossed over the pass the Indians had suggested in the spring. At the

winter camp, a Crow Indian chief told them of the pass through the Wind River

Mountains. Charles Keemle,

a member of Smith’s party, later described what they had been told, "that

a pass existed in the Wind River Mountains, through which he could easily take

his whole band upon streams on the other side. He [the Chief] also represented

beaver so abundant upon these rivers that traps were unnecessary to catch them-they

could club as many as they desired."

“After

two costly failures to gain an foothold on the upper Missouri, Ashley [in 1823]

sent Jedediah Smith and a party of trappers to explore the Crow country and the

region along the Continental Divide. Almost a year passed before several of

Smith's party, led by Thomas Fitzpatrick, stumbled into Ft. Atkinson after an

exhausting journey through South Pass and down the Platte. They brought word

that the mountains were rich with beaver. Responding quickly, Ashley outfitted

a company of trappers and, in November 1824, struck out from Ft. Atkinson via

the Platte Valley for the Rocky Mountains.”

That route, Union Pass, had too much snow to permit

travel across the range. Later, according to Clyman, in another attempt to

communicate with the Crows, sand was strewn on a buffalo robe and a map was

drawn in the sand showing the Wind River Mountains and the location of another

route around them. This was the way to the rich beaver country Smith was

searching for... the Green River and its tributaries.

In late March 1824, with winter's snow still deep on

the ground, Smith's band of men made their way across the windswept desolation

of South Pass and camped in the sage-brush, dining on a freshly killed buffalo.

The next night they camped on the Big Sandy - cold, tired, and hungry. Trying

to chop a hole in the ice so that the men and horses could get a drink was

taking too long, so Clyman took his gun and blasted a hole through with a

bullet. They had successfully crossed the Continental Divide where thousands of

wagons would follow in succeeding decades. A few days later, the party reached

the banks of the Green River

Bridger

left his employment from the Henry Train after three years service (April 1822

– April 1825) and started out on his own in the spring of 1825. Fitzpatrick,

his companion, had been with Smith and others when they had earlier met with

some Crow Indians, who said they should follow the Plain Indian trail to South

Pass, and there they would find many buffalo.

The date of departure disagrees with other diary statements

indicating that Bridger was still with the Ashley group at that time. See

below.

Discovery of the Great Salt Lake

- 1824

·

In the winter of 1824-1825, a group of American Fur

trappers, including Jim Bridger, met up with members of the Missouri Fur

Company comprised of Ashley, Henry & Others. Jim was their guide, and he

followed the course of the Bear River that eventually led to the lake. After

tasting the water Jim thought it might an inland arm of the Pacific Ocean.

Others in 1826, using

skin boats, explored the inland sea in pursuit of Beaver. None were found. Jim

has been given credit for the discovery.

·

Baron Horton [French Governor of Newfoundland],

in 1690 navigated the Mississippi and recorded the apparent first record of the

Great Salt Lake. There he met native tribes from the Mozeemlek Nation, who told

him of a great inland salt sea. “The sea measured 300 leagues in circumference,

and its mouth is two leagues wide.” The Spaniards made the next record in 1872,

in a document called “A Description of the Province of Carolana.” Jim Bridger’s

discovery was actually the third recorded sighting.

·

“The discovery of the Great Salt Lake has

generally been attributed to Jim Bridger, but his partner Louis Vasquez stated

in an October 1858 interview presented in The New York Times and the San

Francisco Bulletin, that he and several other

trappers had first seen the lake in 1822. However, Vasquez confused his

dates and could not have been in the region until years later in the winter of

1825-26. He was known to have been in St. Louis the previous season when

Ashley's party first reached the Great Salt Lake Valley, thus couldn’t possibly

have been there when he claimed.

·

In the fall of 1824, Jim Bridger was reported to

be at Cache Valley, Franklin (Idaho) where the Bear River starts. He made a

Bullboat and floated downstream to the lake. The following year, on May 2nd,

John Weber’s group of Rocky Mountain Fur Company trappers were located at

Franklin, and reported that this was where Bridger camped the previous winter.

The voyage apparently started as a bet as to where the Bear River actually

went. This event took place apparently just before Etienne Provost made his

sighting, and was independent from the Ashley Expeditions that took place

later. This is probably why Bridger was given the recent credit for the

discovery.

o

Ashley left Fort Atkinson on the 3rd November

1824.

“On the afternoon of the fifth, I overtook my party of mountaineers

(twenty-five in number), who had in charge fifty pack horses, a wagon and

teams, etc. On the 6th we had advanced within miles of the villages of the

Grand Pawney's, when it commenced snowing, and continued with but little

intermission until the morning of the 8th. During this time my men and horses

were suffering for the want of food, which, combined with the severity of the

weather, presented rather a gloomy prospect. I had left Fort Atkinson under a

belief that I could procure a sufficient supply of provisions at the Pawney

villages to subsist my men until we could reach a point affording a sufficiency

of game; but in this I was disappointed, as I learned by sending to the

villages, that they were entirely deserted, the Indians having, according to

their annual custom, departed some two or three weeks previous for their

wintering ground. As the vicinity of those villages afforded little or no game,

my only alternative was to subsist my men on horse meat, and my horses on

cottonwood bark, the ground being at this time covered with snow about two feet

deep.”

·

Etienne Provost, however, was trapping the Utah

Lake outlet (Jordan River) area in October 1824 when a Shoshoni war party

attacked and killed eight in his company of ten men. Provost's camp placed him

in sight of the Great Salt Lake several months before Bridger reached the

valley with Ashley's outfit. (Years later, mountain man William Marshall

Anderson added his voice when he wrote the National Intelligencer insisting

that to Provost belonged the credit for having first seen and made known the

existence and whereabouts of the inland sea. (And in July 1897, J.C. Hughey of

Bellevue, Iowa, wrote to The Salt Lake Tribune claiming that John H.

Weber, a onetime Danish sea captain, had been in the mountains in 1822 as a fur

trapper and had in later years often told Hughey he had discovered the lake in

1823. In addition, Hughey wrote, the captain also discovered Weber Canyon and

Weber River, both of which bear his name. (Weber described the lake as

"a great boon to them, as salt was plentiful around the border of the

lake, and for some time before they had used gunpowder on their meat, which was

principally buffalo…")

·

“In 1824, Mr. Ashley

repeated the 1823 expedition, extending it this time beyond Green River as far

as Great Salt Lake, near which to the South he discovered another smaller lake,

which he named Lake Ashley, after himself. On the shores of this lake he built

a fort for trading with the Indians, and leaving in it about one hundred men,

returned to St. Louis the second time with a large amount of furs. During the

time the fort was occupied by Mr. Ashley's men, a period of three years, more

than one hundred and eighty thousand dollars worth of furs were collected and

sent to St. Louis.”

From Col Ashley’s Letter to General Atkinson, December 1,

1825

·

“On the 1st day of july, all the men in my

employ or with whom I had any concern in the country, together with

twenty-nine, who had recently withdrawn from the Hudson Bay company, making in

all 120 men, were assembled in two camps near each other about 20 miles distant

from the place appointed by me as a general rendezvous, when it appeared that

we had been scattered over the territory west of the mountains in small

detachments from the 38th to the 44th degree of latitude, and the only injury

we had sustained by Indian depredations was the stealing of 17 horses by the

Crows on the night of the 2nd april, as before mentioned, and the loss of one

man killed on the headwaters of the Rio Colorado, by a party of Indians

unknown.

·

Mr. Jedediah Smith, a very intelligent and

confidential young man, who had charge of a small detachment, stated that he had,

in the fall of 1824, crossed from the headwaters of the Rio Colorado to Lewis

fork of the Columbia and down the same about one hundred miles, thence

northwardly to Clark's fork of the Columbia, where he found a trading

establishment of the Hudson Bay company, where he remained for some weeks. Mr.

Smith ascertained from the gentleman who had charge of that establishment, that

the Hudson Bay company had then in their employment, trading with the Indians

and trapping beaver on both sides of the Rocky mountains, about 80 men, 60 of

whom were generally employed as trappers and confined their operations to that

district called the Snake country, which Mr. Smith understood as being confined

to the district claimed by the Shoshone Indians. It appeared from the account

that they had taken in the last four years within that district eighty thousand

beaver, equal to one hundred and sixty thousand pounds of furs.

·

Comment: “Jedediah S. Smith and six companions had shadowed the Ogden camp

much of the time since December 29, 1824. The fact that the Americans headed

upstream [during this season] while Ogden and his party turned downstream is of

significance in view of the fact that it virtually excludes Smith from any

claim he may have (or numerous writers have claimed for him) to the honor of

having discovered Great Salt Lake. Several men saw it before he could have

arrived at its shores. Kittson's accurate description of the geographical

features [in his journals] helps materially in locating the actual campsites. This

crossing is just about two miles south of Alexander, Idaho. It is the only

place immediately below the great bend of Bear River where the stream could be

reached and forded because of the high precipitous banks of lava rock.”

‘You

can form some idea of the quantity of beaver that country once possessed, when

I tell you that some of our hunters had taken upwards of one hundred in the